Monmouth, Illinois

Monmouth | |

|---|---|

City | |

Patton Block Building in Monmouth | |

| Nickname: The Maple City | |

| Motto: Make it Monmouth! | |

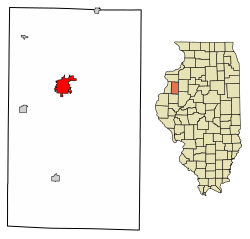

Location of Monmouth in Warren County, Illinois. | |

Location of Illinois in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 40°54′50″N 90°38′33″W / 40.91389°N 90.64250°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Illinois |

| County | Warren |

| Township | Monmouth |

| Area | |

• Total | 4.26 sq mi (11.04 km2) |

| • Land | 4.24 sq mi (10.99 km2) |

| • Water | 0.02 sq mi (0.05 km2) |

| Elevation | 751 ft (229 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 8,902 |

| • Density | 2,098.54/sq mi (810.31/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code(s) | 61462 |

| Area code | 309 |

| FIPS code | 17-50010 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2395371[1] |

| Wikimedia Commons | Monmouth, Illinois |

| Website | cityofmonmouth |

Monmouth is a city in and the county seat of Warren County, Illinois, United States.[3] The population was 8,902 at the 2020 census, down from 9,444 in 2010. It is the home of Monmouth College and contains Monmouth Park, Harmon Park, North Park, Warfield Park, West Park, South Park, Garwood Park, Buster White Park and the Citizens Lake & Campground. It is the host of the Prime Beef festival,[4] held annually the week after Labor Day. The festival is kicked off with one of the largest parades in Western Illinois. Monmouth is also known regionally as the "Maple City". It is part of the Galesburg Micropolitan Statistical Area.

History

[edit]Monmouth was settled in about 1824.[5] The town established in 1831 was originally going to be called Kosciusko (the name was drawn out of a hat), but the founders of the town feared that it would be difficult to spell and pronounce. The name 'Monmouth' was put forward by a resident who had lived in Monmouth County, New Jersey.[6]

In 1841, Latter Day Saint movement founder Joseph Smith appeared before Judge Stephen A. Douglas in an extradition hearing held at Monmouth's Warren County courthouse. The hearing, which was to determine whether Smith should be returned to Missouri to face murder charges, resulted in freedom for the defendant, as it was determined that his arrest had been invalid. Attorney Orville Browning, who would assume Douglas's Senate seat following his death, represented Smith.

Gunfighter and law man Wyatt Earp was born in Monmouth. Controversial Civil War general Eleazer A. Paine practiced law there for many years. Abner C. Harding, Civil War General and Republican Congressman, lived in Monmouth and is buried in Monmouth Cemetery.[7] Ronald Reagan lived in Monmouth for a while as a child when his father worked as a shoe salesman at the Colwell Department Store. Mass murderer Richard Speck lived in Monmouth briefly as a child, and again in the spring of 1966.

Monmouth College, a private liberal arts college affiliated with the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), was founded in Monmouth in 1853 by Cedar Creek & South Henderson Presbyterian Churches. With James Cochran Porter & Robert Ross founding in 1852 Monmouth Academy, The Rev. David Alexander Wallace served as the first President 1856–1878. It is the second-largest employer in the city. Pi Beta Phi, the first national secret college society of women to be modeled after the Greek-letter fraternities of men, was founded on its campus in 1867. Just three years later in 1870, Kappa Kappa Gamma, international fraternity for women, was founded on its campus.[8]

Monmouth was home to minor league baseball from 1890 to 1913. The Monmouth Browns and Monmouth Maple Cities (1890) played as members of the Central Association (1910–1913), Illinois-Missouri League (1908–1909), Central Interstate League (1889) and Illinois-Iowa League (1890). Monmouth teams played at 11th Street Park.[9]

A hospital is located in Monmouth.[5]

Monmouth was once home to one of the most unusually named high school sports organizations, the Zippers. Originally known as The Maroons, the Zipper nickname came about in the late 1930s when the school had a fast basketball team that would "Zip" up and down the court. Earl Bennett, a sportswriter nicknamed them "The Zippers" and the name stuck. The school went with the "Zipper" nickname until the 2004–2005 school year when Monmouth consolidated with Roseville and the new Monmouth–Roseville High School adopted the nickname "The Titans". The class of 2005 was the last class named the Zippers. The Class of 2006 was the first class named the Titans.

Monmouth was the home of Western Stoneware, known for its "Maple Leaf" imprint and for producing "Sleepy Eye" collectible ceramics, which are recognizable by the blue-on-white bas-relief Indian profile. Western Stoneware closed in June 2006. Three former employees of Western Stoneware now operate the facility under the name "WS", Incorporated and have leased the building and logo from the city of Monmouth.[10]

Geography

[edit]Monmouth is located in Western Illinois where US Route 34, US Route 67, Illinois Route 164, and now the new Chicago to Kansas City Expressway (Illinois Route 110) intersect.

According to the 2010 census, Monmouth has a total area of 4.231 square miles (10.96 km2), of which 4.21 square miles (10.90 km2) (or 99.5%) is land and 0.021 square miles (0.05 km2) (or 0.5%) is water.[11]

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Monmouth, Illinois (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

73 (23) |

88 (31) |

93 (34) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

93 (34) |

82 (28) |

72 (22) |

110 (43) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 31.4 (−0.3) |

36.2 (2.3) |

49.7 (9.8) |

62.8 (17.1) |

72.9 (22.7) |

81.2 (27.3) |

84.1 (28.9) |

82.8 (28.2) |

77.3 (25.2) |

64.8 (18.2) |

49.2 (9.6) |

36.5 (2.5) |

60.7 (15.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 23.1 (−4.9) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

39.4 (4.1) |

51.3 (10.7) |

61.9 (16.6) |

70.8 (21.6) |

73.8 (23.2) |

72.2 (22.3) |

65.4 (18.6) |

53.5 (11.9) |

39.9 (4.4) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

50.6 (10.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 14.7 (−9.6) |

18.7 (−7.4) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

39.7 (4.3) |

50.9 (10.5) |

60.3 (15.7) |

63.6 (17.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

53.6 (12.0) |

42.2 (5.7) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

40.5 (4.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−27 (−33) |

−14 (−26) |

10 (−12) |

25 (−4) |

33 (1) |

43 (6) |

38 (3) |

18 (−8) |

7 (−14) |

−4 (−20) |

−22 (−30) |

−27 (−33) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.85 (47) |

1.98 (50) |

2.61 (66) |

3.95 (100) |

5.18 (132) |

4.53 (115) |

3.96 (101) |

3.92 (100) |

3.70 (94) |

3.01 (76) |

2.58 (66) |

2.15 (55) |

39.42 (1,001) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 8.7 (22) |

6.1 (15) |

3.3 (8.4) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

1.4 (3.6) |

4.8 (12) |

25.6 (65) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.0 | 6.6 | 8.1 | 9.9 | 11.8 | 9.6 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 98.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 2.9 | 12.5 |

| Source: NOAA[12][13] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 797 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,506 | 214.4% | |

| 1870 | 4,662 | 86.0% | |

| 1880 | 5,000 | 7.3% | |

| 1890 | 5,936 | 18.7% | |

| 1900 | 7,460 | 25.7% | |

| 1910 | 9,128 | 22.4% | |

| 1920 | 8,116 | −11.1% | |

| 1930 | 8,666 | 6.8% | |

| 1940 | 9,096 | 5.0% | |

| 1950 | 10,193 | 12.1% | |

| 1960 | 10,372 | 1.8% | |

| 1970 | 11,022 | 6.3% | |

| 1980 | 10,706 | −2.9% | |

| 1990 | 9,489 | −11.4% | |

| 2000 | 9,841 | 3.7% | |

| 2010 | 9,444 | −4.0% | |

| 2020 | 8,902 | −5.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 9,841 people, 3,688 households, and 2,323 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,442.3 inhabitants per square mile (943.0/km2). There were 3,986 housing units at an average density of 989.2 per square mile (381.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.72% White, 2.80% African American, 0.23% Native American, 0.47% Asian, 0.19% Pacific Islander, 1.91% from other races, and 1.67% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.35% of the population.

There were 3,688 households, out of which 29.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.7% were married couples living together, 11.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.0% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.37 and the average family size was 2.99.

In the city the population was spread out, with 23.0% under the age of 18, 17.1% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 15.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 88.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.3 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $33,641, and the median income for a family was $41,004. Males had a median income of $30,006 versus $20,144 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,839. About 8.0% of families and 11.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 14.5% of those under age 18 and 6.1% of those age 65 or over.

Transportation

[edit]Burlington Trailways provides intercity bus service to the city on a route between Indianapolis and Denver.[16]

Media

[edit]Radio

[edit]- WMOI-FM (97.7) (RDS) Format: Adult Contemporary

- WRAM-AM (1330)/FM (94.1) Format: News/Talk/Ag Classic Country Music

- WPFS (105.9) "Proud Fighting Scots Radio" Format: Monmouth College Radio

- WKAY-FM (105.3) "Today's Refreshing Light Rock"

- WAAG-FM (94.9) "The Country Station"

- WLSR-FM (92.7) "Pure Rock The Laser"

- WGIL-AM (1400/93.7 FM) "News, Talk, Sports"

Newspaper

[edit]- Daily Review Atlas

- Penny Saver

Culture

[edit]Museums and Galleries

[edit]- The Warren County History Museum

- The Buchanan Center for the Arts

- Holt House (Pi Beta Phi founding house museum)

- Stewart House (Kappa Kappa Gamma founding house museum)

Notable people

[edit]- John Clayton Allen – U.S. Congressman from Illinois from 1925 to 1933

- George A. Beecher – bishop of Western Nebraska[17]

- Ken Blackman – Former NFL football player for the Cincinnati Bengals & Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Grew up in Monmouth.

- Clarence F. Buck – Illinois state senator, farmer, postmaster, and newspaper editor

- Montgomery Case – bridge builder

- Ellen Irene Diggs – American anthropologist and author of African-American history. Born and raised in Monmouth

- Charles Dryden – early 20th Century sportswriter

- Jug Earp – NFL football player from 1921 to 1932

- Wyatt Earp – legendary lawman of the American West; born in Monmouth

- Loie Fuller – pioneer of modern dance

- Gladys Gale – singer and actress

- Ralph Greenleaf – nineteen-time world pocket billiards (Straight Pool) champion (1919–1938) in Hall of Fame

- Regis Groff – second African American elected to the Colorado Senate, lived in Monmouth as a child[18][19]

- J. P. Machado – former NFL football player for the New York Jets

- Mike Miller – basketball coach

- Loren E. Murphy – Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court and mayor of Monmouth

- Eleazer A. Paine – Civil War general, lived in Monmouth

- Ronald Reagan – 40th President of the United States, lived in Monmouth as a child[20]

- James Montgomery Rice – Illinois Congressman, helped establish United States National Guard

- James H. Rupp – Illinois state senator, Mayor of Monmouth, and businessman[21]

- Richard Speck – mass murderer, briefly lived in Monmouth[22]

- Lawrence H. Stice – Illinois state representative and businessman, lived in Monmouth[23]

- John Twomey – manualist

- J. Mayo Williams – pro football player, music producer in Blues Hall of Fame; grew up in Monmouth

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Monmouth, Illinois

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Welcome | Prime Beef Festival".

- ^ a b "1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Monmouth (Illinois) - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org (11th ed.). 1911. p. 727 (Volume 18). Retrieved December 25, 2024.

- ^ History: What's in a Name?, Monmouth Illinois website. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ Congress, United States; Printing, United States Congress Joint Committee on (April 12, 1950). "Biographical Directory of the American Congress, 1774–1949: The Continental Congress, September 5, 1774, to October 21, 1788, and the Congress of the United States from the First to the Eightieth Congress, March 4, 1789 to January 3, 1949, Inclusive". U.S. Government Printing Office – via Google Books.

- ^ "About | Monmouth College". ou.monmouthcollege.edu.

- ^ Rankin, Jeff. "Baseball was favorite summer pastime in early Monmouth". Daily Review Atlas.

- ^ "OsCommerce". Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "G001 – Geographic Identifiers – 2010 Census Summary File 1". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 27, 2015.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Monmouth, IL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Illinois Bus Stops". Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Bishop beecher is Dead; Served Here". The Sidney Telegraph. June 19, 1951. p. 15. Retrieved November 7, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tammi E. Haddad and Merrie Jo Schroeder, Regis Groff Papers: Finding Aid, Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library, Denver Public Library, 2006.

- ^ "Tribute to State Senator Regis Groff". Capitol Words. Archived from the original on October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ Janssen, Kim. "Is Ronald Reagan's Chicago boyhood home doomed?". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on December 2, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 1985–1986,' Biographical Sketch of James H. Rupp, p. 114.

- ^ Breo, Daniel L.; Martin, William J.; Kunkle, Bill (1993). The Crime of the Century: Richard Speck and the Murders That Shocked a Nation. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-56025-1.

- ^ 'Illinois Blue Book 1935–1936,' Biographical Sketch of Lawrence H. Stice, pp. 196–197.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 727.