University of Aberdeen

Coat of arms of the University of Aberdeen | |

| Latin: Universitas Aberdonensis[1] | |

| Motto | Latin: Initium sapientiae timor domini |

|---|---|

Motto in English | The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom |

| Type | Public research university Ancient university |

| Established | 1495 |

| Endowment | £65.3 million (2024)[2] |

| Budget | £264.0 million (2023/24)[2] |

| Chancellor | Queen Camilla |

| Rector | Iona Fyfe |

| Principal | George Boyne |

Academic staff | 1,655 (2022/23)[3] |

Administrative staff | 1,920 (2022/23)[3] |

| Students | 15,455 (2022/23)[4] |

| Undergraduates | 9,715 (2022/23)[4] |

| Postgraduates | 5,740 (2022/23)[4] |

| Location | , Scotland, UK 57°09′55″N 02°06′08″W / 57.16528°N 2.10222°W |

| Campus | Urban, across two main sites |

| Colours | Burgundy and white (university colours) Gold and royal blue (sports colours) |

| Affiliations | |

| Mascot | Angus the Bull |

| Website | abdn |

The University of Aberdeen (abbreviated Aberd. in post-nominals; Scottish Gaelic: Oilthigh Obar Dheathain) is a public research university in Aberdeen, Scotland. It was founded in 1495 when William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen and Chancellor of Scotland, petitioned Pope Alexander VI on behalf of James IV, King of Scots to establish King's College,[5] making it one of Scotland's four ancient universities and the fifth-oldest university in the English-speaking world. Along with the universities of St Andrews, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, the university was part of the Scottish Enlightenment during the 18th century.

The university as it is currently constituted was formed in 1860 by a merger between King's College and Marischal College, a second university founded in 1593 as a Protestant alternative to the former. The university's iconic buildings act as symbols of wider Aberdeen, particularly Marischal College in the city centre and the crown steeple of King's College in Old Aberdeen. There are two campuses; the predominantly utilised King's College campus dominates the section of the city known as Old Aberdeen, which is approximately two miles north of the city centre. Although the original site of the university's foundation, most academic buildings apart from the King's College Chapel and Quadrangle were constructed in the 20th century during a period of significant expansion. The university's Foresterhill campus is next to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and houses the School of Medicine and Dentistry as well as the School of Medical Sciences. Together these buildings form one of Europe's largest health campuses.[6] The annual income of the institution for 2023–24 was £264 million of which £56.9 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £188.9 million.[2]

Aberdeen has educated a wide range of notable alumni, and the university played key roles in the Scottish Reformation, Scottish Enlightenment, and the Scottish Renaissance. Five Nobel laureates have since been associated with the university: two in Chemistry, one in Physiology or Medicine, one in Physics, and one in Peace.[7]

History

[edit]King's and Marischal Colleges

[edit]

There appears to have existed in Old Aberdeen, from a very early period, a studium generate, or university, attached to the episcopal chapter of the See of Aberdeen. It is said to have been founded in 1157 by Edward, Bishop of Aberdeen, and although, according to Hector Boece, it still existed at the period when King's College was founded, it is probable that it had in some way ceased to answer the purposes which it must have been designed to serve, since King James IV, in his letter to Pope Alexander VI, requesting him to found a university in Old Aberdeen, mentions as the chief motive for the undertaking, the profound ignorance of the inhabitants of the north of Scotland, and the great deficiency of properly educated men to fill the clerical office in that part of his kingdom.[8]

The first university in Aberdeen, King's College, formally The university and King's College of Aberdeen (Collegium Regium Aberdonense), was founded on 10 February 1494 by William Elphinstone, Bishop of Aberdeen, Chancellor of Scotland, and a graduate of the University of Glasgow drafting a request on behalf of King James IV to Pope Alexander VI resulting in a papal bull being issued.[5] It seems that James was keen to ensure that Scotland had as many universities as England at the time, and it was to possess all the privileges enjoyed by those of Paris and Bologna, two of the most highly favoured in Europe. The university, modelled on that of the University of Paris and intended principally as a law school, soon became the most famous and popular of the Scots seats of learning, largely due to the prestige of Elphinstone and his friend, Hector Boece, the first principal appointed in 1500. Its aim was to train doctors, teachers and clergy who would serve the communities of northern Scotland, as well as lawyers and administrators for the Scottish Crown. It was a collegiate foundation with 36 full-time staff and students and walls protecting it from the outside world.[9] In 1497 the college established the first chair of medicine in the English-speaking world.

The first book (there was no printing press in Scotland at the time) to be printed in Edinburgh and in Scotland was the Aberdeen Breviary, which was written by both Elphinstone and Boece in 1509.[10]

Following the Scottish Reformation in 1560, King's College was purged of its Roman Catholic staff but in other respects was largely resistant to change. George Keith, the fifth Earl Marischal, was a moderniser within the college and supportive of the reforming ideas of Peter Ramus and Andrew Melville.[11] In April 1593 he founded a second university in the 'New Town', Marischal College. It is also possible the founding of the Fraserburgh University in nearby Fraserburgh by Sir Alexander Fraser, a business rival of Keith, was instrumental in its creation. Aberdeen was highly unusual at this time for having two universities in one city: as 20th-century university prospectuses observed, Aberdeen had the same number as existed in England at the time (the University of Oxford and University of Cambridge).

Initially, Marischal College offered the principal of King's College a role in selecting its academics, but this was refused – the first blow in a developing rivalry. Marischal College, in the commercial heart of the city (rather than the ancient but much smaller collegiate enclave of Old Aberdeen), was quite different in nature and outlook. For example, it was more integrated into the life of the city, such as allowing students to live outwith the college. The two rival colleges often clashed, sometimes in court, but also in brawls between students on the streets of Aberdeen. Duncan Liddell endowed the first chair in mathematics at Marischal College in 1613, but the first professor was not appointed until 1626.

As the institutions put aside their differences, a process of attempted (but unsuccessful) mergers began in the 17th century. During this time, both colleges made notable intellectual contributions to the Scottish Enlightenment. Both colleges supported the Jacobite rebellion and following the defeat of the 1715 rising were largely purged by the authorities of their academics and officials.

King Charles' University (1641–61) and the merger of the two colleges (1860)

[edit]

The nearest the two colleges had come to full union was as the Caroline University of Aberdeen, a merger initiated by Charles I in 1641, which united the two colleges for twenty years. Following the civil conflicts of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a more complete unification was attempted following the ratification of Parliament by Oliver Cromwell during the interregnum in 1654. This united university survived until the Restoration whereby all laws made during this period were rescinded by Charles II and the two colleges reverted to independent status.[12] Charles I is still recognised as one of the university's founders, due to his part in creating the Caroline University and his benevolence towards King's College.[13]

The Aberdeen Philosophical Society (known locally as the Wise Club) was created by Thomas Reid, George Campbell, David Skene, John Gregory, John Stewart, and Robert Traill, and held its first meeting in the Old Red Lion Inn on 12 January 1758. From its inception, the society was an intimate, private body whose members were drawn exclusively from the learned professions, and this feature differentiated it from the more open and socially inclusive societies like the Glasgow Literary Society or the Select Society of Edinburgh. Over 133 papers were given and discussed at the meeting, and many of these formed the basis of books subsequently published. The society was eventually disbanded in March 1773. The society and its individual members played a key role in the Scottish Enlightenment, and it was the most important forum for the promotion of enlightened thought and values in Aberdeen.[14] The Philosophical Society was revived in 1840, with the object of receiving and debating original scientific, literary and philosophical papers from its members; however, the decision was taken on 13 September 1939 to discontinue its meetings, chiefly in view of the difficulties posed by the war, although it does not appear to have been ever formally wound up.[15]

The Free Church of Scotland founded Christ's College in Aberdeen in 1843 for the training of ministers. An extravagant Gothic building, with a commanding oriel window and tower, was erected for the college at the western end of Union Street in 1850. Linked to the college was a museum and library (containing 17,000 volumes).[16] Following the church reunion of 1929, Christ's College became a Church of Scotland college and was integrated into the University of Aberdeen. The college building is no longer used by either the church or the university, and the college is contained completely within the buildings of King's College, maintaining its own divinity library. The university hosted its first meeting of the British Science Association in 1859. Having no suitable meeting place to host the meeting, the town raised the money themselves by personal subscription and built the Music Hall.[17] It was capable of holding about 2,500 people and so successful was the meeting that associate membership, necessary to gain access to the proceedings, had to be capped. Prominent among the local organisers were Professors James Clerk Maxwell (Natural Philosophy) and James Nicol (Geology) of Marischal College. Prince Albert, the Prince Consort, took on the role of president for the year. The young Maxwell himself, still only 28, spoke on three different subjects, one being a presentation of his newly discovered law of molecular velocities in a gas. The 'Maxwell distribution law', as it is now known, is the law of physics with the strongest Aberdeen connection. In addition, Sir Charles Lyell, president of the Geological Section of the British Academy, and a champion Charles Darwin's work, made one of the first announcements that Darwin had undertaken a body of work on evolution and was about to release his findings. The organisers felt that they might be risking something in holding the meeting much further north than they had done before but in the event the Aberdeen meeting was the most well attended the BA had ever had.[18]

Further unsuccessful suggestions for union were brought about throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries.[12] William Ogilvie, known as the Rebel Professor, proposed a paper on the union and reform of the two colleges in 1787, but the proposals were rejected by seven (known as the 'seven wise Masters') out of ten professors at King's.[19] The evolving examination system and university research now required much higher academic standards from the students. The two colleges in Aberdeen merged on 15 September 1860 in accordance with the Universities (Scotland) Act 1858, which also created a new medical school at Marischal College. The 1858 Act of Parliament stated the "united University shall take rank among the Universities of Scotland as from the date of erection of King's College and University." The university is thus Scotland's third oldest and the United Kingdom's fifth oldest university.

The transference of the arts classes from Marischal to King's College required the extension of King's at the cost of £20,000. This included the rebuilding of two sides of the quadrangle for the class-rooms (1862) and the erection of the library (1870), which for many years had occupied the nave of the chapel.[20]

In 1873, university students voted against university degrees being open to women.[21] However, all faculties were open to women in 1892, and in 1894 the first 20 matriculated females began their studies at the university. Four women graduated in arts by 1898, and by the following year, women made up a quarter of the faculty.[22]

The modern university

[edit]

The closing of the quadrangle of Marischal College was completed during the university's quatercentenary in 1906, which was officially opened by Edward VII and Alexandra, and which saw some of the most extravagant celebrations and expressions of civic pride ever demonstrated in Aberdeen.[23] Four days of festivities took place across the city, which included church services, banquets, torchlight processions, and fireworks displays. In all, the cost of the four days of festivities was the modern equivalent of £1.34 million. The ceremony saw the granting of honorary degrees to over a hundred public and academic figures from across the academic world.[24] In an extravagant display of luxury, Lord Strathcona, the then chancellor of the university, spent £8518 in entertaining around 2500 invited guests in a tent specially designed for the occasion.[25] After having received an honorary degree (LLD) in 1905, Thomas Hardy celebrated Aberdeen as 'a University which can claim in my opinion to an exceptional degree that breadth of view & openness of mind that all Universities profess to cultivate, but many stifle'. Hardy wrote a poem for a special number of the student publication, Alma Mater, in celebration of the quatercentenary of the university.[26]

'I looked and thought, "All is too gray and cold

To wake my place-enthusiasms of old!"

Till a voice passed: "Behind that granite mien

Lurks the imposing beauty of a Queen."

I looked anew; and saw the radiant form

Of Her who soothes in stress, who steers in storm,

On the grave influence of whose eyes sublime

Men count for the stability of the time'

In the 20th century, the university expanded greatly, particularly at King's College. New buildings were constructed on the land around King's College throughout the 20th century. Initially, these were built to match the ancient buildings (e.g. the New King's lecture rooms and Elphinstone Hall), but later ones from the 1960s onward were constructed in brutalist style. Meanwhile, the Foresterhill campus began to train medical students in the 1930s next to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.

During the mid-20th century departments which had been at Marischal College moved into one of these new buildings (most at King's College) and by the late 20th-century Marischal College had been abandoned by all but the Anatomy Department, a graduation hall and the Marischal Museum (Marischal College has now been restored as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council, which is leasing a portion of the complex from the university). Following extensive fundraising, a £57 million new university library (the Sir Duncan Rice Library) opened in autumn 2011 at the King's College campus to replace the outgrown Queen Mother Library[27] and was officially opened by the Queen in September 2012.[28] Today, most students spend most of their time in modern buildings which provide up-to-date facilities for teaching, research and other activities such as dining. However, the old buildings at King's College are still in use as lecture and tutorial rooms and accommodation for various academic departments.

In February 2020, the Scottish Funding Council (SFC) found that in approving a financial settlement agreement with the former Principal Sir Ian Diamond, the university failed to make best use of public funds or exercise good governance. As a result of the investigation, the university was ordered to repay £119,000 of grant finance to the SFC and undertake an externally-facilitated examination of its governance and culture.[29]

Modern Languages

[edit]On 5 December 2023 it was announced that a working group, chaired by Professor Karl Leydecker, had been set up to look at the future of teaching of modern languages at the University. It was looking at three options,[30] "all of which involve the end of single honours French, Gaelic, German and Spanish",[31] and was engaging in consultation with student and faculty. It was stated that departmental "income does not cover even the direct costs of staff delivering Modern Languages provision before any central costs ... leading to a projected deficit for Modern Languages of £1.64m in 2023/24."[30] The financial statements were contested by staff and UCU.[32] At an online meeting of the University Senate on 6 December, senators voted 78–15 in favour of a motion which "called for an immediate halt in the consultation process until an overall plan is presented in detail to Senate for appropriate scrutiny." Five senators abstained.[33] On 8 December The Gaudie reported that staff had been sent 'Risk of Redundancy' letters which stated that staff who are made redundant would receive four months pay. This contrasts with the University's severance policy which states that "the maximum redundancy package available to staff is 12 months of pay or £100,000; whatever is lower."[34]

A group of academics from the department released a statement which described the proposed changes as "institutional vandalism". They continued "The management's self-destructive plan would see the University of Aberdeen become the first ancient university in the world not to offer language degrees in one of the most monolingual countries" [35]

A University statement said: "Our difficulty is that this academic year, following longer term declining demand in the UK for traditional specialist language study, a total of just five students began Single Honours across our four Modern Language programmes including Gaelic."[36]

A public petition to save Modern Languages gained over 18,600 signatures.[37] After the submission of two motions calling to protect languages degrees at the University of Aberdeen,[38] a debate took place in Scottish Parliament,[39] where the University was urged to explore alternative options.[40] EU consulates also spoke out in favour of the languages programmes.,[41] as well as scome of Scotland's best-known folk music starts.[32] The local UCU branch successfully balloted for strike action at the University, in support of Modern Languages degrees.[42] Staff-led business proposals were positively received and the consultation on Modern Languages was ended in March 2024 with the removal of risk of compulsory redundancies.[43][44]

Buildings and campuses

[edit]The university's main campus is at King's College in Old Aberdeen, where the original buildings are still in use in addition to many 20th century buildings. A second campus at Foresterhill accommodates the School of Medicine, Medical Science and Nutrition.[45] In addition, there are smaller facilities at other sites such as the Royal Cornhill Hospital to the west of the city centre, and the Rowett Institute in Bucksburn.

Current campuses

[edit]King's College

[edit]

The King's College campus covers an area of some 35 hectares around the ancient King's College buildings and the High Street. It hosts around two-thirds of the university's built estate and most student facilities, and lies 2 miles north of Aberdeen city centre.[45] The university does not own all the buildings on the "campus" which also include private houses, shops and businesses (although many of these rely heavily on custom from the university community) and it is best thought of as a district of the city dominated by the university. It can be reached from the city centre by bus routes 1, 2, 13, 19 and 20 operated by First Aberdeen and from northern Aberdeenshire or Aberdeen bus station by various routes operated by Stagecoach Bluebird.

The historic King's College buildings form a quadrangle with an interior court, two sides of which have been rebuilt and expanded with a library wing in the 19th century. The Crown Tower and the chapel, the oldest parts, date from around 1500. The original foundation contained the chapel, the Great Hall and living accommodation, with its own kitchen and brewery, a well in the quadrangle, and a college garden to provide herbs and vegetables. The Grammar School was just outside the walls, in front of the college. The Crown Tower is surmounted by a structure about 40 ft (12 m) high, consisting of a six-sided lantern and Imperial crown, both sculptured, and resting on the intersections of two arched ornamental slips rising from the four corners of the top of the tower. This crown, also known as the "Crown of Kings", frequently acts as a symbol of the university. The choir of the chapel contains original oak-canopied stalls, miserere seats, and lofty open screens in the French flamboyant style. They were preserved by the college's Principal during the Reformation, who fought off local barons who had attacked the nearby St Machar's Cathedral. The Cromwell Tower, created between 1658 and 1662 opposite the Crown Tower, was originally built as residential accommodation, but an observatory was built on top in 1826.[46] The library wing was converted into an exhibition and conference venue in the 1990s and today also houses the university's Business School.

The first of the modern age of construction in the King's campus began with the construction in 1913 of the New Building (now known as "New King's"), largely in a similar architectural style to the old buildings. A large manse located on the lawn opposite King's College was removed before the First World War.[47] New King's groups to form a yet larger quadrangle-like green for the campus also bordered by the High Street, King's and Elphinstone Hall, a traditional 1930 replacement for the Great Hall. The Elphinstone Hall was subsequently used as a dining facility but is now used for graduations, examinations, fairs, and other large university events.

However, most students and staff spend relatively little time in these historic buildings, with a large number of modern ones housing most facilities and academic departments. Most date from the second half of the 20th century. Some of these echo the existing architecture of Old Aberdeen, such as the Fraser Noble Building with its distinctive concrete crown designed to resemble the one adorning King's College. Other buildings were constructed of stone in the 1950s (e.g. the Taylor Building and Meston Building). A number of other buildings are designed in the brutalist style, such as the Arts Lecture Theatre and adjoining William Guild Building, opened in 1969 to house the School of Psychology. Also on the site is the Cruickshank Botanic Garden which was presented to the university in 1899 and is open to the public.

The Powis Gateway forms the east gate and archway from College Bounds, Old Aberdeen. These oriental style towers with minarets have provoked much interest over the years. At one time there was a portrait of John Leslie dressed in Turkish costume, on the walls of Powis House, but there is no obvious connection between the estate and the Middle East. The gateway is also adorned with panels bearing the coats of arms of the Lairds of Powis. The Estate of Powis was owned by the Frasers—their crest is shown on the towers—until the marriage of an heiress to a Leslie. Powis House was built by Hugh Leslie. The house was the home of John Leslie, Professor of Greek at Kings College. It was subsequently owned by the Burnett family. In 1936, J.G. Burnett sold most of the estate to Aberdeen Town Council who built a housing estate in the area comprising over 300 residences.[48]

The Sir Duncan Rice Library was designed by Danish architects Schmidt Hammer Lassen and completed in 2011. It was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in September 2012 and named after Duncan Rice, a previous Principal of the university.[28] This seven-storey tower, clad in zebra-like jagged stripes of white and clear glass, replaced the smaller Queen Mother Library as the university's main library and can be seen prominently from the entire campus and much of the city. It is open to the public and outstanding views of the city and coastline are available from the upper floors. In addition to expanded facilities it also houses public exhibition space and the university's historic collections, comprising more than a quarter of a million ancient and priceless books and manuscripts collected over five centuries since the university's foundations.[49] Other libraries are in the Taylor Building on the same campus (for law books and materials) and at Foresterhill (for medicine and medical sciences). The university's library service (i.e. including all libraries) holds over one million books.

The most recent building is the Science Teaching Hub. Completed in 2021, the building contains laboratories for subjects including biological sciences, chemistry, geosciences and medical sciences.[50]

The Aberdeen Sports Village, located across King Street from the Old Aberdeen campus, houses sports facilities and the aquatics centre.

Foresterhill

[edit]

The university's Foresterhill Campus is located approximately 1.75 kilometres (1.09 mi) to the east of the Old Aberdeen campus and is home to the university's Life Sciences and Medicine facilities. It is co-located with Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Royal Aberdeen Children's Hospital and Aberdeen Maternity Hospital, all teaching hospitals operated by regional health board NHS Grampian. The campus accommodates the School of Medicine, Medical Science and Nutrition; the School of Psychology; and the School of Biological Sciences. It also includes the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, the Institute of Medical Sciences, Institute of Applied Health Sciences, Institute of Dentistry, and Institute of Education for Medical & Dental Sciences.[51]

The Foresterhill site is managed jointly with NHS Grampian. The university has had a presence at Foresterhill since around 1938, and the management of the site was formalised in 1997 by the completion of an operational agreement between the two parties.[52]

Doha, Qatar

[edit]A new campus in Doha, Qatar was established in May 2017. Known as AFG College with the University of Aberdeen, it is a partnership with Al Faleh Group for Educational and Academic Services (AFG). The courses currently offered are accounting, finance and business management. The campus Principal is Brian Buckley.[53]

Former campuses

[edit]Marischal College

[edit]

Marischal College is a neo-Gothic building, having been rebuilt in 1836–41, and greatly extended several years later. Formerly an open three-sided court, the college now forms a quadrangle as additions to the buildings were opened by Edward VII in 1906 and form the current facade from Broad Street. The building is widely considered to be one of the best examples of neo-Gothic architecture in Great Britain; the architect, Alexander Marshall Mackenzie was a native of Aberdeen as well as an alumnus of the university. The Mitchell Tower at the rear is named for the benefactor (Dr Charles Mitchell) who paid for the graduation hall. The opening of this tower in 1895 was part of celebrations of the 400th anniversary of the university.

Until 1996, Marischal College housed the Departments of Molecular & Cell Biology and Biomedical Sciences, which had been there for many decades. From 1996, the departments moved to Kings College campus and Foresterhill campus. Teaching no longer takes place at Marischal College, with many of the departments formerly based there having moved to King's College some decades previously. While graduations and other events (e.g. concerts) took place in the cathedral-like Mitchell Hall in the north wing, for many years much of the building (including the frontage to the street) was derelict.

The majority of the building was leased to Aberdeen City Council in 2008, with significant re-development taking place to allow the council to occupy it as its new administrative headquarters.[54] Occupation of the rear portion of the building is retained by the university including the former Marischal Museum and Mitchell Hall, which was used previously for graduation and other academic ceremonies before moving to Elphinstone Hall at King's College.[45]

Hilton

[edit]A small campus at Hilton became part of the university estate following a merger in 2001 between the university and the Aberdeen campus of the Northern College of Education, and temporarily became home to the university's Faculty of Education. It was less than a mile southwest of King's College campus.[45] Following the renovation of the MacRobert Building at King's College to house the School of Education (completed in 2005), the Hilton campus was closed and sold to developers.[55] The campus was demolished and the land is now occupied by a residential development called "The Campus".

Organisation and administration

[edit]Governance

[edit]

In common with the other ancient universities in Scotland, the university's structure of governance is largely regulated by the Universities (Scotland) Acts of 1858. This gives the university a tripartite constitution comprising the General Council of senior academics and graduates, the University Court responsible for finances and administration, and the Academic Senate (Senatus Academicus)—the university's supreme academic body. There are correspondingly three main officers of the university. It is nominally headed by the chancellor, a largely ceremonial position traditionally held by the Bishop of Aberdeen, but as a result of the Scottish Reformation holders are now elected for life by the General Council. There is also a rector of the university, who chairs the University Court and is elected by the students for a three-year term to represent their interests. There are also four assessors, ten masters, including the principal and vice principal, and the factor or procurator.

The administrative head and chief executive of the university is its principal and vice-chancellor. The principal acts as chair of the Senatus Academicus, and his status as vice-chancellor enables him to perform the functions reserved to the chancellor in the latter's absence, such as the awarding of degrees.

University officials

[edit]The university's three most significant officials are its chancellor, principal, and rector, whose rights and responsibilities are largely derived from the Universities (Scotland) Act 1858.

The chancellor is the nominal head of the university. The chancellor since 2013 is Queen Camilla.[56] She is the first female chancellor of the university. The chancellor, or, if necessary, his or her deputy, confers degrees on graduates and chairs the university's General Council.

The principal and vice-chancellor of the university is Professor George Boyne. He joined the university on 1 August 2018 and was officially installed in his role on 16 January 2019.[57]

The rector of the university has been—since 1860—elected by the students to serve a three-year term of office; before that, the office was appointed. The rector's duties are to chair meetings of the University Court and to represent student views on that body.[citation needed] In November 2024, Iona Fyfe, a Scottish folk singer, was elected by the student body of the university as the new rector.[58] Other notable Aberdeen rectors have included Winston Churchill, Andrew Carnegie, H. H. Asquith, Maggie Chapman and Clarissa Dickson Wright, who was Aberdeen's first female rector.[59][60]

The University Court

[edit]This body was created by the commissioners during the merger of King's and Marischal in 1870. It was part of a series of reforms introduced to rectify the method of government, with the Court acting as a court of appeal from the Senatus.[61] The Court originally consisted of six members; the rector, representing the students, the principal, and one assessor each to the chancellor, the rector, the General Council and the Senatus. However, today the Court consists of many more members.[62] The Court's principal role is to oversee the management of the revenue, property and other resources of the university.

Senatus Academicus

[edit]The Academic Senate (Latin: Senatus Academicus) is the supreme academic body for the university. Its members include all the professors of the university, certain senior readers, a number of senior lecturers and lecturers and elected student senate representatives. It is responsible for authorising degree programmes and issuing all degrees to graduates, and for managing student discipline. The president of the Senate is the university principal.

Schools and Institutes

[edit]The university is divided into 12 schools which are organised within a broad range of disciplines, with the larger schools sub-divided into three teaching colleges.

Multi-disciplinary institutes and research centres allow the university's experts to collaborate on pioneering research projects.

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Institute of Medical Sciences, Aberdeen

-

Chemistry Department

-

Cruickshank Building

-

Edward Wright Building

-

Fraser Noble Building

-

Geography Department

-

History Department

-

Faculty of Education

-

The Rowett Institute

-

A mosaic of the University of Aberdeen coat of arms on the floor of King's College

Finances

[edit]In the financial year ending 31 July 2024, Aberdeen had a total income of £264 million (2022/23 – £268.6 million) and total expenditure of £188.9 million (2022/23 – £259.3 million).[2] Key sources of income included £91.3 million from tuition fees and education contracts (2022/23 – £96.9 million), £76.8 million from funding body grants (2022/23 – £80.4 million), £56.9 million from research grants and contracts (2022/23 – £56.3 million), £5.1 million from investment income (2022/23 – £3.4 million) and £3.8 million from donations and endowments (2022/23 – £0.7 million).[2]

At year end, Aberdeen had endowments of £65.3 million (2023 – £58.6 million) and total net assets of £431 million (2023 – £352.4 million).[2]

Symbols of the university

[edit]The university's coat of arms is an integral part of the current logo, which along with the colours burgundy and white, is used extensively on campus signage, printed materials, and online.

Coat of arms

[edit]The university's coat of arms incorporates those of the founders and locations of the two colleges it is derived from. In the top left quadrant are the arms of the burgh of Old Aberdeen, with the addition of a symbol of knowledge being handed down from above. Top right are those of George Keith, the fifth Earl Marischal. Bottom left are those of Bishop William Elphinstone.[63] The bottom right quarter is a simplified version of the three castles which represent the city of Aberdeen[64] (this symbol of the city also appears prominently on the arms of The Robert Gordon University).

Motto

[edit]The motto of the University of Aberdeen is Initium Sapientiae Timor Domini, which translates from Latin as "The beginning of wisdom is fear of the Lord". It is a quote from the Old Testament of the Bible, Psalm 111, verse 10. It also appears in the Book of Proverbs (9:10). The motto can be seen at the archway beside New King's on the High Street at the King's College campus, as well as other campus locations and in formal settings such as on graduation certificates.

Tartan

[edit]A university tartan was created in 1992 as part of the celebrations for the 500th anniversary of the university which took place in 1995. The tartan was designed by the Weavers Incorporation of Aberdeen and Harry Lindley and incorporates colours from the university's coat of arms.[65]

Academic dress

[edit]

Academic dress has been worn in the University of Aberdeen since mediaeval times.[66] Aberdeen shared with the other ancient universities the wearing of scarlet gowns (toga rubra) and a trencher for undergraduates, but by the middle of the twentieth century its use amongst the students had faded.[67] Bursars formerly wore a black gown, and were made to perform menial services about college. Female students wore a trencher with scarlet tassels, while male students wore black tassels.[68]

Academic dress is usually worn only at formal occasions, such as at graduation, Founder's Day, or academic processions which take place for ceremonial reasons. For undergraduate degrees (e.g. MA, BSc, LLB etc.), a long black gown is worn with a hood of black silk and lined with silk in a colour which varies depending on discipline. For example, the lining is white silk for all Master of Arts degrees, green silk for Bachelor of Science in pure sciences, and crimson silk for MBChB. A black mortarboard is also worn. For master's degrees (e.g. MSc, MLitt etc.) a long black gown is worn, with a white silk hood lined in a colour that varies by discipline. For PhD, the doctor's scarlet robe is worn with black facings and sleeve lining, along with a black "John Knox" cap. For other doctoral degrees (e.g. EdD, LLD etc.), the scarlet robe has facings and sleeve linings in a different colour.

Academics

[edit]Term

[edit]The academic year at Aberdeen was originally based upon the Scottish Term and Quarter Days, beginning with Martinmas (October – November), Candlemas (January – March), and ending with Whitsunday (April – June). However, today the academic term is divided into two semesters, the First Half-Session and the Second-Half Session, beginning in September and ending in May. Written examinations are sat in November and April and May, and graduation is celebrated either in November or at the end of June.[69]

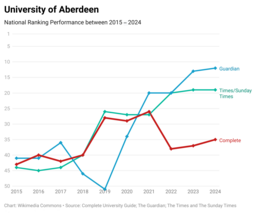

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[70] | 40 |

| Guardian (2025)[71] | 12 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2025)[72] | 15 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[73] | 201–300 |

| QS (2025)[74] | 236= |

| THE (2025)[75] | 201–250 |

Aberdeen is consistently ranked among the top 200 universities in the world[76] and is ranked within the top 20 universities in the United Kingdom according to The Guardian.[77][78] In the 2019 Times Higher Education University Impact Rankings, Aberdeen was ranked 31st in the world for impact on society.[79] Aberdeen was also named the 2019 Scottish University of the Year by The Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide.[80] Over 75 per cent of the university's research was classified as 'world leading' or 'internationally excellent' in the 2014 Research Excellence Framework.[81]

Its highest internationally ranked subject is Divinity and Religious Studies, which is ranked at joint 25th in the world and 7th in the UK.[82] It also has an excellent reputation for medical research and many of its subjects are ranked in top 10 in the UK, including Accounting & Finance (ranked 4th in the UK, Complete 2021), Civil Engineering (10th in the UK, Complete 2021), Computing Science (9th in the UK, Guardian 2021), Dentistry (9th in the UK, Complete 2020; 1st in the UK, Guardian 2021), Education (9th in the UK, Complete 2021), Electrical and Electronic Engineering (8th in the UK, Complete 2020), Law (6th in the UK, Complete 2021; 10th in the UK, Guardian 2021), Medicine (4th in the UK, Complete 2021; 2nd in the UK, Guardian 2021), Linguistics (5th in the UK, Complete 2021), Musics (10th in the UK, Guardian 2021), Physics (7th in the UK, Guardian 2021), Sociology (10th in the UK, Guardian 2021), and Sports Science (2nd in the UK, Complete 2021; 10th in the UK, Guardian 2021).[83] Economics was ranked 11th in the UK by Times Subject Rankings[84] and 12th in the UK by Complete University Guide 2019.[85]

Admissions

[edit]

|

| Domicile[89] and Ethnicity[90] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British White | 60% | ||

| British Ethnic Minorities[a] | 12% | ||

| International EU | 9% | ||

| International Non-EU | 19% | ||

| Undergraduate Widening Participation Indicators[91][92] | |||

| Female | 59% | ||

| Private School | 16% | ||

| Low Participation Areas[b] | 8% | ||

Aberdeen was ranked 9th for the average entry tariff by the Complete University Guide 2021[93] and 10th in the UK for the average entry tariff by Guardian 2025 rankings.[94]

The university has one of the smallest percentages of students from lower-class backgrounds, being ranked fifth from bottom for class equality.[95][96] The university participates in widening access schemes such as the Children's University, REACH Scotland, Access Aberdeen, and ASPIRENorth, in order to promote a more widespread uptake of those traditionally under-represented at university.[97]

Lecture series

[edit]The Gifford Lectures, established in 1887 by Adam Gifford, began at the university (along with the other ancient universities in Scotland) with E.B Tylor's lecture on the Natural History of Religion between 1889 and 1991. Since then, over 30 Gifford Lectures have been given at the university, with some distinguished figures including Hannah Arendt, Alfred North Whitehead, Karl Barth, Paul Tillich, Michael Polanyi, N.T. Wright, and Jaroslav Pelikan.[22]

A public lecture series was held in 2011 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the publication of the King's James Bible.[98] The university is also host to the annual Andrew Carnegie Lecture Series which began in 2014, with the first lecture given by Matthew Barzun.[99]

The Elphinstone Institute hosts its own monthly lecture series, which began in 2016, in the MacRobert Building, with lectures usually given on local or Scottish topics. (The Elphinstone Institute also organises The Toulmin Prize, a short-fiction competition with a North East Scotland focus that is open to amateur writers.) The School of Engineering also hosts the RV Jones Distinguished Lecture Series which provides invited lectures from distinguished speakers in areas of engineering related to research within the School of Engineering.[100]

Libraries and Museums

[edit]The library was first located in the nave of King's College Chapel and then moved to a new site in the college in 1870.[101] The current library contains one of the most extensive university library collections in the United Kingdom, with over a million volumes and a quarter of a million ancient and priceless books and manuscripts, including the Hortus sanitatis.[102] The library at Aberdeen was given the right of legal deposit under the Statute of Anne (1710) but this was rescinded in 1837, and as a result has a rare collection of pre-Victorian novels.[103] The core of the original library at King's College was formed from Elphinstone's books that he left to the university. The books were originally housed in a room in the south east tower (now the round tower). They were then moved to a building on the south side of Kings College Chapel, and in 1773 to the west end of the chapel. They were located in 1870 to a new building as illustrated. This library was extended in 1885, with galleries being installed in 1912, reading desks in 1932 and a mezzanine floor in 1964.[104] The Queen Mother Library had been the university's main library since 1965, and the original library in King's College was replaced with the King's College Conference Centre in 1991. The Queen Mother Library was refurbished and expanded in 1982.[105]

The Sir Duncan Rice Library was officially opened on 24 September 2012 by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh, replacing the Queen Mother Library. It was designed by the Danish architectural firm Schmidt Hammer Lassen at the cost of £57 million. The building sits on a base of Scottish stone. The ground floor is double-height with seven floors above. The building is clad in zebra-like jagged stripes of white and clear glass. In the interior void spaces are located centrally. Contrasting with the geometric exterior, the central atrium formed by the void spaces has an organic form, shifting in location across the levels. It has won numerous awards for its architecture.[106]

The university also has the Taylor Law Library which is located in the Taylor Building in Old Aberdeen, and the Medical Library on the Foresterhill Campus, which covers the Medicine and Medical Sciences disciplines.[107] Christ's College also possesses its own Divinity library.

The university maintains several museums and galleries, open free to the public.[108] The university's collections are internationally renowned and are recognised as of national significance by the Scottish Government. Originating in the eighteenth century, they now have over 300,000 items across a wide range of Human Culture, Medicine and Health, and Natural History. The Zoology Museum is officially classified as a Recognised Collection of national significance to Scotland and features displays from protozoa to the great whales, including taxidermy, skeletal material, study skins, fluid-preserved specimens and models.

Student life

[edit]As of 2022/23 the university had 15,455 students, of which 5,740 were postgraduates.[4] In 2009/10 students represented 120 countries with about 46% men, 54% women. Of all of undergraduates, 19% were mature students (i.e. aged 25 years or more). The university has more than 550 different undergraduate degree programmes and more than 120 postgraduate taught programmes.[7]

Students' Association

[edit]

The student body is represented by a students' association known as Aberdeen University Students' Association (AUSA). Additionally, the elected Rector of the University of Aberdeen serves along with the AUSA president and another sabbatical officer as students' representatives on the University Court.

AUSA does not operate a traditional students' union, instead operating out of a university building, The Students Union Building, formerly The Hub, helping to support students and provide events and studying space. A large students' union formerly occupied an impressive granite building on the corner of Gallowgate and Upperkirkgate in the city centre, opposite Marischal College, but it closed in 2003. A second, smaller union opened at nearby Littlejohn Street a couple of years later, but by 2010 it too had closed.[109]

The organisation has been involved in the creation of "The Hub", a university-owned dining and social centre created by an extensive renovation of the former Central Refectory at the King's College campus. It provides facilities for the whole university community (students and staff) and opened in 2006. A more traditional social space, the Butchart Student Centre, opened in 2009. It acts as the HQ of the Students' Association and provides a wide range of student facilities, but due to city council licensing regulations there is no bar. The Butchart Centre includes facilities for student societies and offices. The Butchart Centre was converted from what had been the campus sports centre before the opening of the Aberdeen Sports Village nearby. AUSA operates out of the Johnston Building.[citation needed]

"BookEnds" which sells second-hand books with profits going towards charity was initially established in the Butchart Recreation Centre but now operates in the AUSA building.

Student societies and organisations

[edit]There are over a hundred clubs and societies formally affiliated with the students' association.[110] The students' association is responsible for sport at the university, which is managed by the Aberdeen University Sports Union, an AUSA committee. All registered students are eligible to join any of these clubs or societies.

The university's oldest student organisation is the Aberdeen University Debater, founded by JF Maclennan in 1848 as the King's College Debating Society.[111][112][113] In 1871, a Literary Society was started by WM Ramsay, and four years later a Choral Society came to life.[114] In 1884, the society also took the first steps towards the introduction of a students' representative council under support from Alexander Bain, the then Rector. The creation of the Union in 1895 provided a new debating chamber in Marischal College and the society's first permanent home. The chamber beneath Mitchell Hall in Marischal College is Scotland's oldest purpose-built debating chamber.[citation needed]

In 1998, an alumni fund called the Aberdeen Future Fund was founded, run by the Development Trust. It has raised over £2.5 million of unrestricted funds. Past projects have included a book fund for the Heavy Demand section in the library, providing "Safe Campus" leaflets, contributing to the student hardship fund, providing training mannequins for Clinical Skills, the organ for King's College Chapel, and funding for intramural sports.[115]

Sports clubs and the Sports Union

[edit]

The students' association is responsible for sport at the university, which is managed by the Aberdeen University Sports Union, an AUSA committee. Established in 1889, it is affiliated to the BUCS and SSS and encompasses over fifty sports clubs.[116] There are large playing fields at the back of King's College and also Aberdeen Sports Village, a partnership between the University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen City Council and sportscotland. It opened on 22 August 2009.[117] An extension containing the aquatics centre opened on 5 May 2014.[118][119]

The Aberdeen University Football Club was formed in 1872, and currently competes in the SJFA North First Division. The Aberdeen University Rugby Football Club was founded in 1871, and has a long history of producing both Scottish and British Lions players.[citation needed]

The annual boat race between Aberdeen University Boat Club and Robert Gordon University Boat Club has been competed for since 1995. The University of Aberdeen has lost only four times, in 2006, 2009, 2012 and 2013.

Aberdeen Sports Village served as one of the official pre-games training venues of the Cameroon Olympic Team prior to the London 2012 Olympic Games.[120]

Music

[edit]There are a large number of ensembles at the University of Aberdeen. Some are directed by academic staff, while others are run by students both in and out of the department and include; Balinese Gamelan, Baroque Ensemble, Big Band, Cantores ad Portam, Chapel Choir, Choral Society, Concert Band, String Orchestra and Symphony Orchestra.[citation needed]

The Aberdeen Student Show is a musical and theatrical show, usually with a strong comedy element, staged every year since 1921. Its purpose is to raise money for charity, as part of the Aberdeen Students' Charities Campaign. A number of its writers, performers and musicians have gone on to greater renown in the fields of theatre, media and the arts.[citation needed]

Student media

[edit]The first successful university newspaper, Alma Mater, began under the auspices of the University of Aberdeen Debating Society in 1883. The Alma Mater was replaced by The Gaudie, which has been in circulation since 1934, and is currently free-of-charge. The Gaudie is recognised as one of the oldest student newspapers in Scotland and the United Kingdom.[citation needed]

The University of Aberdeen also hosts a chapter of Her Campus, a magazine targeted at female students.[121]

Other student media organisations include Granite City TV and Aberdeen Student Radio (ASR).[122]

Celebrations and festivals

[edit]In 2020, the WayWORD Festival[123] was launched by the university's WORD Centre for Creative Writing. This yearly programme celebrates the arts through readings, performances, workshops and discussion panels. It has featured notable headliners including Val McDermid, Irvine Welsh and Douglas Stuart.[citation needed]

Until 2019, each year a student-led torcher parade was held. First held in 1889, it was the largest of its kind in Europe.[124] Student groups and societies build floats and parade in fancy dress through the city centre to raise money for local charities. Traditionally spectators donated money in the form of coppers, a colloquial term for 1p and 2p coins.

University accommodation

[edit]

Halls of residence are managed by the university. Two large concentrations of university accommodation are provided on the campus in Old Aberdeen and one mile north at the Hillhead Student Village, accessible by a walk through Seaton Park.

Campus accommodation in the heart of Old Aberdeen consists of self-catered King's Hall and Elphinstone Road Halls.

The university has a "First-Year Accommodation Guarantee" providing that the student accept their firm offer before a set date prior to the beginning of term.[125] In 2014–15, the university ran out of rooms and had to resort to temporary accommodation.[126] The university continues to monitor accommodation costs and where possible offers discretionary support to students, to improve access to higher education.[citation needed]

Halls of residence include:

- Adam Smith House

- Elphinstone Road Flats

- Fyfe House

- Grant Court

- Hector Boece Court

- Keith House

- Kings Hall

- New Carnegie Court

- North Court

- South House

- Wavell House

The first modern halls of residence built by the university on the King's College campus was Crombie halls, named after James Edward Crombie. They opened in 1960.[127] The Crombie-Johnston halls were closed in 2017 following a decline in demand for catered accommodation.[128]

The Elphinstone Road halls were completed in 1992.[129]

Traditions

[edit]Sponsio Academica

[edit]The Sponsio Academica is the oath, originally in Latin, taken by students matriculating into the four ancient Scottish universities (Edinburgh, St. Andrews, Aberdeen and Glasgow). This tradition now has been digitised at Aberdeen and is agreed to as part of an online matriculation process. Originally, new students matriculated in Mitchell Hall where the Chancellor would give a welcoming address.

Since 1888 the School of Medicine has used a form of the Sponsio Academica for graduating students to affirm in response to the discontinuation of the oath hitherto taken by students in all faculties:[130]

"I solemnly declare that as a Graduate of Medicine of the University of Aberdeen, I will exercise my profession to the best of my knowledge and ability, for the good of all persons whose health may be placed in my care, and for the public weal; that I will hold in due regard the honourable traditions and obligations of the Medical Profession, and will do nothing inconsistent therewith; and that I will be loyal to the University and endeavour to promote its welfare and maintain its reputation.'[131]

Founders' Day

[edit]Usually held annually in February, on Founders' Day, the university community pays tribute to its historic origins as an ancient university and in particular, the role played by William Elphinstone and other benefactors in the establishment of the university. The ceremony begins with an academic procession through the university and concludes with a service in King's College Chapel. Talks are given by university lecturers and invited guests. A candle is lit in the chapel to give thanks to Elphinstone and the other patron fathers.

Installing of the rector

[edit]The rector, an ancient post dating back to the foundation of the university in 1495, is the students' representative, particularly in welfare matters, and sits on the University Court.

Tradition dictates that the University of Aberdeen's new rector must ride through Old Aberdeen aloft a bull carried at shoulder height by students of the university. The ceremony includes a colourful academic procession representing civic, student and academic life in Aberdeen. University staff and students, along with representatives from the City and Aberdeenshire Councils, Incorporated Trades, MSPs, and alumni, attend the ceremony which is followed by a reception in the King's Conference Centre.[132]

The reception culminates with the new Rector being carried by the student mascot, Angus the Bull, from King's College to the St Machar Bar in the High Street of Old Aberdeen, where tradition also dictates that he buy a round of drinks for his student supporters.

Bajan

[edit]Bajan, a medieval term (literally 'yellow beak' – bec jaune), describing trainees in the pre-student year, was traditionally applied to Aberdeen University first year undergraduates. Female undergraduates were referred to as "bajanellas".[133] Second year students were called 'Semis', and these usually played jokes upon or clashed with bajans. Semis would usually tear first year's gowns.[134]

These terms were based on the four years of the degree:

- B first year (bajan)

- S second year (semi)

- T third year (tertian)

- M fourth year (magistrand)[135]

Notable alumni and academics

[edit]This article's list of alumni may not follow Wikipedia's verifiability policy. (August 2019) |

-

Patrick Manson, founder of the field of tropical medicine, the London School of Tropical Medicine, Dairy Farm, and the University of Hong Kong.[142]

-

Alexander Bain, analytical philosopher, psychologist, educationalist, and founder of the first academic psychology and philosophy journal, Mind.[143]

-

Robert Brown, botanist and discoverer of Brownian motion. (Was a student, but did not graduate).[144]

-

John Arbuthnot, scientist, mathematician, court physician to Queen Anne, author, and co-founder of the Scriblerus Club. Fellow of the Royal Society (1704).[145]

-

Sir James Mackintosh, philosopher, historian, and Whig politician.[146]

-

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, jurist and pioneer anthropologist who anticipated principles of Darwinian evolution.[147]

-

James Gregory, discoverer of the infinite series and designer of the first practical reflecting telescope, the Gregorian telescope.[148]

-

James Gibbs, architect. Studied at Marischal College.[151]

-

James Macpherson, writer, poet, politician, and 'translator' of the Ossian cycle of epic poems.

-

Sir Thomas Sutherland, banker, politician, and founder of the Hong Kong Bank and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC).

-

Robert Davidson, inventor of the electric locomotive.

- Nobel Prizes (alumni and faculty)

-

Frederick Soddy, Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

-

John Macleod, Nobel Prize in Medicine

-

George Paget Thomson, Nobel Prize in Physics

-

John Boyd Orr, Nobel Peace Prize

-

Richard Laurence Millington Synge, Nobel Prize in Chemistry

See also

[edit]- Ancient universities

- Armorial of UK universities

- List of medieval universities

- List of universities in the United Kingdom

- 5677 Aberdonia, minor planet named after the University of Aberdeen

Notes

[edit]- ^ Includes those who indicate that they identify as Asian, Black, Mixed Heritage, Arab or any other ethnicity except White.

- ^ Calculated from the Polar4 measure, using Quintile1, in England and Wales. Calculated from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) measure, using SIMD20, in Scotland.

References

[edit]- ^ Anderson, Peter John (1907). Record of the Celebration of the Quatercentenary of the University of Aberdeen: From 25th to 28th September, 1906. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Aberdeen University Press (University of Aberdeen). ASIN B001PK7B5G. ISBN 9781363625079.

- ^ a b c d e f "Annual Reports & Accounts 2024" (PDF). University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ a b "Who's working in HE?". www.hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c d "Where do HE students study?". Higher Education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ a b Bulloch, John Malcolm (1895). A History of the University of Aberdeen: 1495–1895. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "Medicine – University of Aberdeen". Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ a b "Fast Facts". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ^ Gregory, William (1845). The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845).

- ^ For a summary description of all of the set of scholars and literati who intervened in teaching at the old University of Aberdeen, see David de la Croix and Hugo Jay,(2021). Scholars and Literati at the Old University of Aberdeen (1495–1800).Repertorium Eruditorum Totius Europae/RETE. 4: 27–34.

- ^ Bulloch, John Malcolm (1895). A history of the University of Aberdeen : 1495–1895. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 14.

- ^ "This Noble College: Building on the European tradition". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ a b "The New Statistical Account of Scotland – Account of the University and King's College of Aberdeen". Electricscotland.com. Archived from the original on 9 October 2024. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "Founders' Day Service". Public Relations, University of Aberdeen, pubrel@abdn.ac.uk. 9 November 2004. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ Wood, Paul (2006). "Aberdeen Philosophical Society". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95092 – via Oxford DNB. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Aberdeen Philosophical Society". The Doric Columns. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Alford Plaxe, The College (former Christ's College) (LB20086)".

- ^ Jones, RV (1973). "James Clerk Maxwell at Aberdeen". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 28: 64. JSTOR 531113.

- ^ "Aberdeen celebrates the 150th anniversary of Advancement of Science in the Granite City". The University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023.

- ^ MacDonald, DC (1997). Birthright in Land: Ogilvie. Palala Press.

- ^ Bulloch, John (1895). A history of the University of Aberdeen. London : Hodder and Stoughton. p. 198.

- ^ Rayner-Canham, Geoffrey (2020). Pioneering British Women Chemists: Their Lives And Contributions. World Scientific Europe. p. 235.

- ^ a b "University of Aberdeen". Gifford Lectures. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016.

- ^ "The Quatercentenary celebrations, 1906". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021.

- ^ "The Quatercentenary Celebrations of the University of Aberdeen" (PDF). Nature. 74 (1927): 565–567. 1906. Bibcode:1906Natur..74..565.. doi:10.1038/074565a0. S2CID 3973978. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2023.

- ^ "The Quatercentenary celebrations, 1906". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Ray, Martin. "Thomas Hardy in Aberdeen".

- ^ "The Sir Duncan Rice Library". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Queen opens new library at Aberdeen University". BBC News. 24 September 2012. Archived from the original on 27 February 2023. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Grove, Jack (18 February 2020). "Aberdeen told to repay £119K over ex-head's 'gardening leave'". Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ a b "The future of Modern Languages at the University of Aberdeen | News | The University of Aberdeen". www.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Ross, Calum (4 December 2023). "Scottish Government urges Aberdeen University to 'carefully consider' plans to axe languages degrees". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ a b Carrell, Severin (8 December 2023). "Folk music stars join protests over plans to axe Gaelic at Aberdeen University". The Guardian.

- ^ Gaudie, The (7 December 2023). "Senate Calls For Consulation Halt in Rebuke of SMT". The Gaudie. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Gaudie, The (8 December 2023). "FOUR MONTHS severance for language staff". The Gaudie. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Williams, Craig (11 December 2023). "Aberdeen University 'will continue to teach languages' amid cuts row". The Herald. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Pooran, Neil (3 January 2024). "Aberdeen University staff to vote on strikes over language course changes". The Standard. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Backlash grows against Aberdeen language cuts". Times Higher Education (THE). 12 December 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Protecting Language Study at the University of Aberdeen". www.parliament.scot. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Scottish Parliament to Debate University of Aberdeen Language Cuts – Aberdeen Business News". 16 January 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Motion to Save UoA Language Degrees Discussed at Scottish Parliament". The Gaudie. 18 January 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "EU consulates call for Aberdeen language courses to be saved". BBC News. 26 November 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Aberdeen University staff vote to strike over languages cuts". BBC News. 7 February 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Strike over language cuts at Aberdeen called off after jobs saved". Times Higher Education (THE). 7 March 2024. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ "Modern Languages staff not facing compulsory redundancy | News | the University of Aberdeen".

- ^ a b c d "Estate Strategy 2002–2007". University Estates Office. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ "History of the Cromwell Tower Observatory". Aberdeen University History.

- ^ "Kings College Chapel and Manse". Silver City Vault.

- ^ "Powis Gateway". The Silver City Vault.

- ^ "Press Release: 'Flagship library project to match academic ambitions' leads next phase of University's infrastructure investment". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ "Science Teaching Hub | Study Here | The University of Aberdeen". www.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ "Campus – Foresterhill". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Appendix B: Overview of Main Campus Sites – Foresterhill". Estates Strategy 2013–2023 (PDF). University of Aberdeen. 2007. p. 36.

- ^ "AFG College with the University of Aberdee". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Marischal College". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ "University seeks "TC" former students and staff for Hilton closing events". University of Aberdeen. 10 June 2005. Retrieved 20 November 2010.

- ^ "Aberdeen University poised to install Duchess of Rothesay Camilla as new Chancellor". Daily Record. 10 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ "Duchess of Cornwall congratulates new principal of University of Aberdeen". HeraldScotland. 16 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ "Scottish folk singer Iona Fyfe named new University of Aberdeen rector". The Herald. 22 November 2024.

- ^ "Rectorial Election | Students' Infohub | The University of Aberdeen". www.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Maggie Chapman named as new University of Aberdeen rector". BBC News. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Bulloch, James (1895). A history of the University of Aberdeen. London : Hodder and Stoughton. p. 198.

- ^ "Court Members". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "University of Aberdeen – Coat of arms (crest) of University of Aberdeen". www.ngw.nl. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "University of Aberdeen – Armorial Tablet". The Heraldry Society of Scotland. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ "Tartan Details – Aberdeen University (1992)". The Scottish Register of Tartans. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ Cooper, J. C., 'Academical Dress in Late Medieval and Renaissance Scotland', Medieval Clothing and Textiles, 12 (2016), pp. 109–30. (Available here)

- ^ Cooper, Jonathan C. (2010). "The Scarlet Gown: History and Development of Scottish Undergraduate Dress". Transactions of the Burgon Society. 10. doi:10.4148/2475-7799.1082.

- ^ Rayner-Canham, Marlene (2020). Pioneering British Women Chemists: Their Lives And Contributions. World Scientific Europe. p. 235.

- ^ "Academic Calendar". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "Complete University Guide 2025". The Complete University Guide. 14 May 2024.

- ^ "Guardian University Guide 2025". The Guardian. 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Good University Guide 2025". The Times. 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2024". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 15 August 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. 4 June 2024.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2025". Times Higher Education. 9 October 2024.

- ^ "University of Aberdeen Rankings". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Top UK University League Tables and Rankings 2019". Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ "University Guide 2016 – The Times". nuk-tnl-editorial-prod-staticassets.s3.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "World Impact Rankings". Times Higher Education (THE). 2 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ "University of Aberdeen named Scottish University of the Year | News | The University of Aberdeen". www.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Research Excellence Framework – University of Aberdeen results". Research Excellence Framework.

- ^ "2020 QS World University Subject Rankings – Theology, Divinity & Religious Studies". nuk-tnl-deck-prod-static.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Top UK University League Tables and Rankings 2020". www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "UK University Times Subject Ranking 2018 – Economics". www.ukuni.net. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Economics – Top UK University Subject Tables and Rankings 2019". www.thecompleteuniversityguide.co.uk. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b "UCAS Undergraduate Sector-Level End of Cycle Data Resources 2023". ucas.com. UCAS. December 2023. Show me... Domicile by Provider. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "2023 entry UCAS Undergraduate reports by sex, area background, and ethnic group". UCAS. 30 April 2024. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "University League Tables entry standards 2024". The Complete University Guide.

- ^ "Where do HE students study?: Students by HE provider". HESA. HE student enrolments by HE provider. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Who's studying in HE?: Personal characteristics". HESA. 31 January 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Widening participation: UK Performance Indicators: Table T2a – Participation of under-represented groups in higher education". Higher Education Statistics Authority. hesa.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ "Good University Guide: Social Inclusion Ranking". The Times. 16 September 2022.

- ^ "2021 University Rankings". The Complete University Guide.

- ^ "University league tables 2020". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ^ Martin, Iain. "Benchmarking widening participation: how should we measure and report progress?" (PDF). HEPI.

- ^ Busby, Eleanor (5 April 2018). "Cambridge and Oxford among worst universities in UK for socio-economic equality, report reveals". The Independent.

- ^ "Widening Access". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "Lecture series commemorates 400th anniversary of the King James Bible". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie Lecture Series". Carnegie Corporation of New York.

- ^ "RV Jones Distinguished Lecture Series". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Bulloch, John (1895). A history of the University of Aberdeen. London : Hodder and Stoughton. p. 196.

- ^ "Sir Duncan Rice Library". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Attar, Karen (2016). Directory of Rare Book and Special Collections in the UK and Republic of Ireland. p. 450.

- ^ "King's College Library, Old Aberdeen". Silver City Vault.

- ^ "Queen Mother to visit library". The Press and Journal. 27 September 1982. p. 15. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Sir Duncan Rice Library". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "Our Libraries, Special Collections and Museums". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "University Museums". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland. "Aberdeen, 11 Gallowgate, Aberdeen University Students' Union (148116)". Canmore.

- ^ "AUSA Societies Union". Aberdeen University Students' Association. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ Anderson, R.D The Student Community at Aberdeen: 1860–1939 (AUP)

- ^ McLaren, C.A. Aberdeen Students 1600–1860 (AUP)

- ^ Hargreaves, J.D. and Forbes, Angela Aberdeen University 1945–1981: Regional Roles and National Needs (AUP)

- ^ Bulloch, James (1895). A history of the University of Aberdeen. London : Hodder and Stoughton. p. 202.

- ^ "Giving to Aberdeen". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Sports Union". University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "£28 million Aberdeen Sports Village to open its doors". University of Aberdeen. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Aberdeen Sports Village About Page". Aberdeen Sports Village. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Aquatics Centre Officially Opens Doors to Public". Sport Scotland. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "London 2012: Aberdeen to host Cameroon preparations". BBC News. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Aberdeen | Her Campus". 19 June 2024. Retrieved 8 July 2024.

- ^ "Aberdeen Student Radio". University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2013.

- ^ "WayWORD Festival". WayWORD Festival. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ "125th anniversary of Aberdeen Torcher Parade". University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Applying for Accommodation | Accommodation | The University of Aberdeen". www.abdn.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Rooms shortage forces university to book new students into hotel". STV News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ "Crombie Hall open to students in April". Evening Express. 5 November 1959. p. 3. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Hendry, Ben (23 October 2017). "University flats lie empty for first time in decades". Press and Journal. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ "You can move in, students told in design row". The Press and Journal. 1 October 1992. p. 26. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Veatch, Robert (2005). Disrupted Dialogue: Medical Ethics and the Collapse of Physician-Humanist Communication. Oxford University Press. p. 32.

- ^ Deblamothe, T (1994). "The Hippocratic Oath". British Medical Journal. 309: 953.

- ^ "New Rector carried aloft to begin new role". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ "The Varsity Spirit: Student Show in the '20s and '30s". The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Rait, Robert (1912). Life in the Medieval University. Forgotten Books. p. 123.

- ^ "Marischal College Guide" (PDF). The University of Aberdeen.

- ^ Broun, Macolm (1995). "George Wishart: a Torch of the Reformation in Scotland". Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History. 3.

- ^ Lorimer, Peter (1923). The Scottish Reformation: A Historical Sketch. p. 91.

- ^ "Thomas Reid". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Robertson, Kirsten (23 November 2018). "Alistair Darling offers wise words to Aberdeen University graduates". Aberdeen press and Journal. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Hebdich, Jon (15 May 2018). "Memories of Dame Tessa Jowell's education in Aberdeen flood in". Aberdeen Press and Journal. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "The Burnet Psalter". Aberdeen University. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Sir Patrick Manson (1844-1922)". London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Alexander Bain (1818-1903)". Institute for the Study of Scottish Philosophy. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ Burbidge, N T. "Brown, Robert (1773–1858)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "John Arbuthnot". MacTutor (History of Mathematics Archive). School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "MS 2164 - Sir James Mackintosh, M.P.: correspondence and biographical notes". Museums and Special Collections, University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714-1799)". The University of Edinburgh. Alumni Services. 29 August 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Who was James Gregory?". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "James Blair Statue, Dedicated 1993". TribeTrek. Special Collections Research Center, William & Mary Libraries. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Dr. William Thornton". Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Friedman, Terry (3 January 2008). "Gibbs [Gibb], James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10604. Retrieved 3 January 2022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Lee, Sidney, ed. (1895). Dictionary of national biography, Vol. 42. New York: Macmillan and Co. p. 21. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "Iain Glen". University of Aberdeen. Alumni Relations. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

![George Wishart, early Protestant reformer[136][137]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/91/GeorgeWishart2.jpg/165px-GeorgeWishart2.jpg)

![Thomas Reid, founder of the Scottish School of Common Sense.[138]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/92/ThomasReid.jpg/186px-ThomasReid.jpg)