Armory Show

Armory show button, 1913 | |

| Date | February 17, 1913 to March 15, 1913 |

|---|---|

| Location | 69th Regiment Armory, New York, NY |

| Also known as | The International Exhibition of Modern Art |

| Participants | Artists in the Armory Show |

The 1913 Armory Show, also known as the International Exhibition of Modern Art, was organized by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors. It was the first large exhibition of modern art in America, as well as one of the many exhibitions that have been held in the vast spaces of U.S. National Guard armories.

The three-city exhibition started in New York City's 69th Regiment Armory, on Lexington Avenue between 25th and 26th Streets, from February 17 until March 15, 1913.[1] The exhibition went on to the Art Institute of Chicago and then to The Copley Society of Art in Boston,[2] where, due to a lack of space, all the work by American artists was removed.[3]

The show became an important event in the history of American art, introducing Americans, who were accustomed to realistic art, to the experimental styles of the European avant garde, including Fauvism and Cubism. The show served as a catalyst for American artists, who became more independent and created their own "artistic language."

"The origins of the show lie in the emergence of progressive groups and independent exhibitions in the early 20th century (with significant French precedents), which challenged the aesthetic ideals, exclusionary policies, and authority of the National Academy of Design, while expanding exhibition and sales opportunities, enhancing public knowledge, and enlarging audiences for contemporary art."[4]

History

[edit]

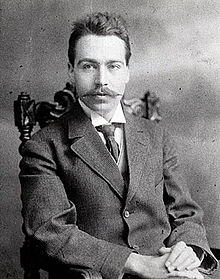

On December 14, 1911, an early meeting of what would become the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS) was organized at Madison Gallery in New York. Four artists met to discuss the contemporary art scene in the United States, and the possibilities of organizing exhibitions of progressive artworks by living American and foreign artists, favoring works ignored or rejected by current exhibitions. The meeting included Henry Fitch Taylor, Jerome Myers, Elmer Livingston MacRae and Walt Kuhn.[5]

In January 1912, Walt Kuhn, Walter Pach, and Arthur B. Davies joined with some two dozen of their colleagues to reinforce a professional coalition: AAPS. They intended the organization to "lead the public taste in art, rather than follow it."[6] Other founding AAPS members included D. Putnam Brinley, Gutzon Borglum, John Frederick Mowbray-Clarke, Leon Dabo, William J. Glackens, Ernest Lawson, Jonas Lie, George Luks, Karl Anderson, James E.Fraser, Allen Tucker, and J. Alden Weir.[6] AAPS was to be dedicated to creating new exhibition opportunities for young artists outside of the existing academic boundaries, as well as to providing educational art experiences for the American public.[1] Davies served as president of AAPS, with Kuhn acting as secretary.[citation needed]

The AAPS members spent more than a year planning their first project: the International Exhibition of Modern Art, a show of giant proportions, unlike any New York had seen. The 69th Regiment Armory was settled on as the main site for the exhibition in the spring of 1912, rented for a fee of $5,000, plus an additional $500 for additional personnel.[7] It was confirmed that the show would later travel to Chicago and Boston.[citation needed]

Once the space had been secured, the most complicated planning task was selecting the art for the show, particularly after the decision was made to include a large proportion of vanguard European work, most of which had never been seen by an American audience.[1] In September 1912, Kuhn left for an extended collecting tour through Europe, including stops at cities in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and France, visiting galleries, collections and studios and contracting for loans as he went.[8] While in Paris Kuhn met up with Pach, who knew the art scene there intimately, and was friends with Marcel Duchamp and Henri Matisse; Davies joined them there in November 1912.[1] Together they secured three paintings that would end up being among the Armory Show's most famous and polarizing: Matisse's Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) and Madras Rouge (Red Madras Headdress), and Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2. Only after Davies and Kuhn returned to New York in December did they issue an invitation for American artists to participate.[1]

Pach was the only American artist to be closely affiliated with the Section d'Or group of artists, including Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Duchamp brothers Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Jacques Villon and others. Pach was responsible for securing loans from these painters for the Armory Show. Most of the artists in Paris who sent works to the Armory Show knew Pach personally and entrusted their works to him.[9] The Armory Show was the first, and ultimately the only exhibition mounted by the AAPS.

In 1913, the art collector and lawyer John Quinn fought to overturn censorship laws restricting modern art and literature from entering the United States. He convinced the United States Congress to overturn the 1909 Payne–Aldrich Tariff Act, which retained the duty on foreign works of art less than 20 years old, discouraging Americans from collecting modern European art. Quinn opened the Armory Show exhibition with the words:

... it was time the American people had an opportunity to see and judge for themselves concerning the work of the Europeans who are creating a new art.[10]

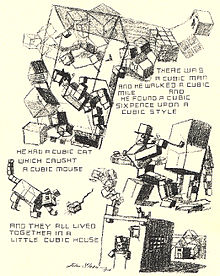

The Armory Show displayed some 1,300 paintings, sculptures, and decorative works by over 300 avant-garde European and American artists. Impressionist, Fauvist, and Cubist works were represented.[11] The publicity that stormed the show had been well sought, with the publication of half-tone postcards of 57 works, including the Duchamp nude that would become its most infamous.[12] News reports and reviews were filled with accusations of quackery, insanity, immorality, and anarchy, as well as parodies, caricatures, doggerels, and mock exhibitions. Some responded with laughter, as the artist John French Sloan seemed to not take the exhibition seriously in his published cartoon, "A slight attack of third dimentia brought on by excessive study of the much-talked of cubist pictures in the International Exhibition at New York".[13] About the modern works, former President Theodore Roosevelt declared, "That's not art!"[14] The civil authorities did not, however, close down or otherwise interfere with the show.[citation needed]

Among the scandalously radical works of art, pride of place goes to Marcel Duchamp's cubist/futurist style Nude Descending a Staircase, painted the year before, in which he expressed motion with successive superimposed images, as in motion pictures. Julian Street, an art critic, wrote that the work resembled "an explosion in a shingle factory" (this quote is also attributed to Joel Spingarn[15]), and cartoonists satirized the piece. Gutzon Borglum, one of the early organizers of the show who for a variety of reasons withdrew both his organizational prowess and his work, labeled this piece A staircase descending a nude, while J. F. Griswold, a writer for the New York Evening Sun, entitled it The rude descending a staircase (Rush hour in the subway).[16] The painting was purchased from the Armory Show by Frederic C. Torrey of San Francisco.[17]

The purchase of Paul Cézanne's Hill of the Poor (View of the Domaine Saint-Joseph) by the Metropolitan Museum of Art signaled an integration of modernism into the established New York museums, but among the younger artists represented, Cézanne was already an established master.[citation needed]

Duchamp's brother, who went by the "nom de guerre" Jacques Villon, also exhibited, sold all his Cubist drypoint etchings, and struck a sympathetic chord with New York collectors who supported him in the following decades.[citation needed]

The exhibition went on to show at the Art Institute of Chicago and then to The Copley Society of Art in Boston,[2] where, due to a lack of space, all the work by American artists was removed.[3]

While in Chicago, the exhibition created a scandal that reached the governor's office. Several articles in the press recounted the issue. In one newspaper the headline read: Cubist Art Will be Investigated; Illinois Legislative Investigators to Probe the Moral Tone of the Much Touted Art:

Chicago, April 2: Charges that the international exhibition of cubist and futurist pictures, now being displayed here at the art institute, contains many indecent canvasses and sculptures will be investigated at once by the Illinois legislature white slave commission. A visit of an investigator to the show and his report on the pictures caused Lieutenant Governor Barratt O'Hara to order an immediate examination of the entire exhibition. Mr. O'Hara sent the investigator to look over the pictures after he had received many complaints of the character of the show. "We will not condemn the international exhibit without an impartial investigation," said the lieutenant governor today. "I have received many complaints, however, and we owe it to the public that the subject be looked into thoroughly." The investigator reported that a number of the pictures were "immoral and suggestive." Senators Woodward and Beall of the commission will visit the exhibition today.

— Ottumwa Tri-Weekly Courier, Iowa, 3 April 1913[18]

Floor plan

[edit]

The following shows the content of each gallery:[19]

- Gallery A: American Sculpture and Decorative Art

- Gallery B: American Paintings and Sculpture

- Gallery C, D, E, F: American Paintings

- Gallery G: English, Irish and German Paintings and Drawings

- Gallery H, I: French Painting and Sculpture

- Gallery J: French Paintings, Water Colors and Drawings

- Gallery K: French and American Water Colors, Drawings, etc.

- Gallery L: American Water Colors, Drawings, etc.

- Gallery M: American Paintings

- Gallery N: American Paintings and Sculpture

- Gallery O: French Paintings

- Gallery P: French, English, Dutch and American Paintings

- Gallery Q: French Paintings

- Gallery R: French, English and Swiss Paintings

Legacy

[edit]The original exhibition was an overwhelming success. There have been several exhibitions that were celebrations of its legacy throughout the 20th century.[20]

In 1944 the Cincinnati Art Museum mounted a smaller version, in 1958 Amherst College held an exhibition of 62 works, 41 of which were in the original show, and in 1963 the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York, organized the "1913 Armory Show 50th Anniversary Exhibition" sponsored by the Henry Street Settlement in New York, which included more than 300 works.[20]

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) was officially launched by the engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer and the artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman when they collaborated in 1966 and together organized 9 Evenings: Theatre and Engineering, a series of performance art presentations that united artists and engineers. Ten artists worked with more than 30 engineers to produce art performances incorporating new technology. The performances were held in the 69th Regiment Armory, as an homage to the original and historical 1913 Armory show.[21][22]

In February 2009, the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA) presented its 21st annual Art Show to benefit the Henry Street Settlement, at the Seventh Regiment Armory, located between 66th and 67th Streets and Park and Lexington Avenues in New York City.[23] The exhibition began as a historical homage to the original 1913 Armory Show.[citation needed]

Starting with a small exhibition in 1994, by 2001 The Armory Show, now held at the Javits Center, evolved into a "hugely entertaining" (The New York Times) annual contemporary arts festival with a strong commercial bent.[citation needed]

Commemorating the centennial

[edit]Many exhibitions in 2013 celebrated the 100th anniversary of the 1913 Armory Show, as well as a number of publications, virtual exhibitions, and programs. The first exhibition, "The New Spirit: American Art in the Armory Show, 1913," opened at the Montclair Art Museum on February 17, 2013, a hundred years to the day from the original.[1] The second exhibition was organized by the New-York Historical Society and titled "The Armory Show at 100," taking place from October 18, 2013, through February 23, 2014.[24] The Smithsonian's Archives of American Art, which lent dozens of historic documents to both the New York Historical Society and Montclair for the exhibitions, created an online timeline of events, 1913 Armory Show: the Story in Primary Sources, to showcase the records and documents created by the show's organizers.[25]

Showing contemporary work, a third exhibition, The Fountain Art Fair, was held at the 69th Regiment Armory itself during the 100th anniversary during March 8–10, 2013. The ethos of Fountain Art Fair was inspired by Duchamp's famous "Fountain" which was the symbol of the Fair.[26] The Art Institute of Chicago, which was the only museum to host the 1913 Armory Show, presented works February 20 – May 12, 2013, the items drawn from the museum's modern collection that were displayed in the original 1913 exhibition.[27] The DePaul Art Museum in Chicago, Illinois presented For and Against Modern Art: The Armory Show +100, from April 4 to June 16, 2013.[28] The International Print Center in New York held an exhibition, "1913 Armory Show Revisited: the Artists and their Prints," of prints from the show or by artists whose work in other media was included.[12]

In addition, the Greenwich Historical Society presented The New Spirit and the Cos Cob Art Colony: Before and After the Armory Show, from October 9, 2013, through January 12, 2014. The show focused on the effects of the Armory Show on the Cos Cob Art Colony, and highlighted the involvement of artists such as Elmer Livingston MacRae and Henry Fitch Taylor in producing the show.[29]

American filmmaker Michael Maglaras produced a documentary film about the Armory Show entitled, The Great Confusion: The 1913 Armory Show. The film premiered on September 26, 2013, at the New Britain Museum of American Art in New Britain, Connecticut.[30]

List of artists

[edit]Below is a partial list of the artists in the show. These artists are all listed in the 50th anniversary catalog as having exhibited in the original 1913 Armory show.[20]

- Robert Ingersoll Aitken

- Alexander Archipenko

- George Grey Barnard

- Chester Beach

- Gifford Beal

- Maurice Becker

- George Bellows

- Joseph Bernard

- Guy Pène du Bois

- Oscar Bluemner

- Hanns Bolz

- Pierre Bonnard

- Solon Borglum

- Antoine Bourdelle

- Constantin Brâncuși

- Georges Braque

- Bessie Marsh Brewer

- Patrick Henry Bruce

- Paul Burlin

- Theodore Earl Butler

- Charles Camoin

- Arthur Carles

- Mary Cassatt

- Oscar Cesare

- Paul Cézanne

- Robert Winthrop Chanler

- Pierre Puvis de Chavannes

- John Frederick Mowbray-Clarke

- Nessa Cohen

- Camille Corot

- Kate Cory

- Gustave Courbet

- Henri-Edmond Cross

- Leon Dabo

- Andrew Dasburg

- Honoré Daumier

- Jo Davidson

- Arthur B. Davies (President)

- Stuart Davis

- Edgar Degas

- Eugène Delacroix

- Robert Delaunay

- Maurice Denis

- André Derain

- Katherine Sophie Dreier

- Marcel Duchamp

- Georges Dufrénoy

- Raoul Dufy

- Jacob Epstein

- Mary Foote

- Roger de La Fresnaye

- Othon Friesz

- Paul Gauguin

- William Glackens

- Albert Gleizes

- Vincent van Gogh

- Francisco Goya

- Marsden Hartley

- Childe Hassam

- Robert Henri

- Edward Hopper

- Ferdinand Hodler

- Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres

- James Dickson Innes

- Augustus John

- Gwen John

- Wassily Kandinsky

- Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

- Leon Kroll

- Walt Kuhn (Founder)

- Gaston Lachaise

- Marie Laurencin

- Ernest Lawson

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Arthur Lee

- Fernand Léger

- Wilhelm Lehmbruck

- Jonas Lie

- Amy Londoner

- George Luks

- Aristide Maillol

- Édouard Manet

- Henri Manguin

- Edward Middleton Manigault

- John Marin

- Albert Marquet

- Henri Matisse

- Alfred Henry Maurer

- Kenneth Hayes Miller

- David Milne

- Claude Monet

- Adolphe Monticelli

- Edvard Munch

- Ethel Myers

- Jerome Myers (Founder)

- Elie Nadelman

- Olga Oppenheimer

- Walter Pach

- Jules Pascin

- Agnes Pelton

- Francis Picabia

- Pablo Picasso

- Camille Pissarro

- Maurice Prendergast

- Odilon Redon

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- Boardman Robinson

- Theodore Robinson

- Auguste Rodin

- Georges Rouault

- Henri Rousseau

- Morgan Russell

- Albert Pinkham Ryder

- André Dunoyer de Segonzac

- Georges Seurat

- Charles Sheeler

- Walter Sickert

- Paul Signac

- Alfred Sisley

- John Sloan

- Amadeo de Souza Cardoso

- Joseph Stella

- Felix E. Tobeen

- John Henry Twachtman

- Félix Vallotton

- Raymond Duchamp-Villon

- Jacques Villon

- Maurice de Vlaminck

- Bessie Potter Vonnoh

- Édouard Vuillard

- Abraham Walkowitz

- J. Alden Weir

- James Abbott McNeill Whistler

- Enid Yandell

- Jack B. Yeats

- Mahonri Young

- Marguerite Zorach

- William Zorach

List of women artists

[edit]Women artists in the Armory Show includes those from the United States and from Europe. Approximately a fifth of the artists showing at the armory were women, many of whom have since been neglected.[31]

Images

[edit]

-

Entrance of the Exhibition, 1913, New York City

-

Interior view of the exhibition, 1913, New York City

-

Interior view of the exhibition, 1913, New York City

-

Armory Show artists and members of the press at the beefsteak dinner given by the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, March 8, 1913. Percy Rainford, photographer. Walt Kuhn family papers and Armory Show records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

-

Installation shot of the Matisse room, 1913 Armory Show, published in the New York Tribune (p. 7), February 17, 1913. From the left: Le Luxe II, 1907–08, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen; "Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra)", 1907, Baltimore Museum of Art; L'Atelier Rouge, 1911, Museum of Modern Art, New York City

-

Installation shot of the Cubist room, published in the New York Tribune, February 17, 1913 (p. 7). Left to right: Raymond Duchamp-Villon, La Maison Cubiste (Projet d'Hotel), Cubist House; Marcel Duchamp Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train; Albert Gleizes, L'Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony; Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2; Alexander Archipenko, La Vie Familiale, Family Life

Selected painting and sculpture

[edit]-

Eugène Delacroix, Christ on the Sea of Galilee, 1854

-

Honoré Daumier, The Third Class Wagon, 1862–1864

-

Édouard Manet, The Bullfight, 1866

-

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black: The Artist's Mother 1871, popularly known as Whistler's Mother, Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Although Whistler was represented by four paintings in the Armory show this was not included.

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, In The Garden 1885, Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

-

Mary Cassatt, Mère et enfant (Reine Lefebre and Margot before a Window), c.1902

-

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, c. 1887, oil on canvas, 40 × 34 cm (15+3⁄4 by 13+3⁄8). Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut

-

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Adeline Ravoux 1890, Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Vincent van Gogh, Mountain in Saint-Rémy, 1889, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

-

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Seacoast in Moonlight, 1890, the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

-

Paul Gauguin, Words of the Devil, 1892, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

-

Paul Gauguin, Nature morte à l'estampe japonaise (Flowers Against a Yellow Background), 1889, oil on canvas, 72.4 × 93.7 cm, Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran

-

Paul Gauguin, Tahitian Pastorals, (Reo Mā`ohi: Faa iheihe (Fa'ai'ei'e)), 1898, National Gallery on loan from the Tate

-

Henri Rousseau, The Centenary of the Revolution, 1892

-

Henri Rousseau, Cheval attaqué par un jaguar (Jaguar Attacking a Horse), 1910, oil on canvas, 116 × 90 cm, Pushkin Museum

-

Edvard Munch, Vampire 1893–94, Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

-

Paul Cézanne, Old Woman with Rosary, 1895–1896

-

Paul Cézanne, Baigneuses, 1877–1878

-

Julian Alden Weir, The Red Bridge, 1895

-

Claude Monet, Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge, 1897–1899

-

John Twachtman, Hemlock Pool, c.1900

-

Henri-Edmond Cross, Cypresses at Cagnes, c.1900

-

Paul Signac, Port de Marseille, 1905, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

André Derain, 1912, Window on the Park (La Fênetre sur le parc), 130.8 × 89.5 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

André Derain, Landscape in Provence (Paysage de Provence) (c. 1908), Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn

-

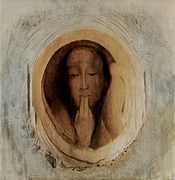

Odilon Redon, Le Silence, 1900, pastel, 54.6 × 54 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

Odilon Redon, Roger and Angelica, 1910

-

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club, 3 ft 9 in (1.14 m) × 5 ft 3 in (1.60 m), National Gallery of Art, 1909

-

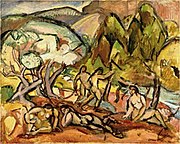

Othon Friesz, Landscape with Figures, 1909, oil on canvas, 65 × 83 cm

-

Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Saut du Lapin, 1911

-

Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Avant la Corrida, 1912, oil on canvas, 60 × 92 cm, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal

-

Robert Winthrop Chanler, Leopard and Deer, 1912, gouache or tempera on canvas, mounted on wood, 194.3 × 133.4 cm, Rokeby Collection

-

Edward Middleton Manigault, The Clown, 1910–12, oil on canvas, 86.4 × 63.2 cm, Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio

-

Patrick Henry Bruce, Still Life, c. 1912

-

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Naked Playing People, 1910

-

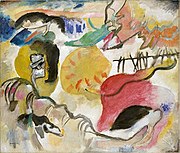

Wassily Kandinsky, Improvisation 27 (Garden of Love II), 1912, oil on canvas, 47+3⁄8 in × 55+1⁄4 in (1,200 mm × 1,400 mm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

-

Maurice Prendergast, Landscape With Figures, 1913

-

Robert Henri, Figure in Motion, 1913

-

Arthur B. Davies, Reclining Woman (Drawing), 1911, Pastel on gray paper

-

Henri Matisse, Le Luxe II, 1907–08, distemper on canvas, 209.5 × 138 cm, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen

-

Pablo Picasso, 1910, Woman with Mustard Pot (La Femme au pot de moutarde), oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

-

Georges Braque, Violin: "Mozart Kubelick", 1912, oil on canvas, 45.7 × 61 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Albert Gleizes, 1910, La Femme aux Phlox (Woman with Phlox), oil on canvas, 81 × 100 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

-

Albert Gleizes, L'Homme au Balcon, Man on a Balcony (Portrait of Dr. Théo Morinaud), 1912, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Published in the Record Herald, Chicago, 25 March 1913 (see page 140)

-

Marcel Duchamp, 1911–1912, Nude (Study), Sad Young Man on a Train (Nu, esquisse, jeune homme triste dans un train), oil on cardboard mounted on Masonite, 100 × 73 cm, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

-

Francis Picabia, Grimaldi après la pluie (believed to be Souvenir of Grimaldi, Italy), c. 1912, location unknown

-

Francis Picabia, The Dance at the Spring, 1912, oil on canvas, 47+7⁄16 by 47+1⁄2 inches (1,205 mm × 1,206 mm), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia

-

Francis Picabia, The Procession, Seville, 1912, oil on canvas, 121.9 × 121.9 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

-

Robert Delaunay, Window on the City, No. 4, 1910–11 (1912)

-

Jacques Villon, 1912, Girl at the Piano (Fillette au piano), oil on canvas, 129.2 × 96.4 cm, oval, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston. Purchased from the Armory Show by John Quinn

-

Aristide Maillol, Bas Relief, terracotta. Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago, Boston. Catalogue image (no. 110)

-

Alexander Archipenko, 1910–11, Negress (La Negresse), Armory Show catalogue photo

-

Alexander Archipenko, La Vie Familiale (Family Life), 1912. Exhibited at the 1912 Salon d'Automne, Paris and the 1913 Armory Show in New York, Chicago and Boston. The original sculpture (approx six feet tall) was accidentally destroyed

-

Alexander Archipenko, Le Repos, 1912, Armory Show postcard published in 1913

-

Constantin Brâncuși, 1909, Portrait De Femme (La Baronne Renée Frachon), now lost. Armory Show, published press clipping, 1913

-

Constantin Brâncuși, 1912, Portrait of Mlle Pogany, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Armory Show postcard

-

Constantin Brâncuși, The Kiss, 1907–1908, published in the Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1913

-

Constantin Brâncuși, Une Muse, 1912, plaster, 45.7 cm (18 in.) Armory Show postcard. Exhibited: New York (no. 618); The Art Institute of Chicago (no. 26) and Boston, Copley Hall (no. 8)

-

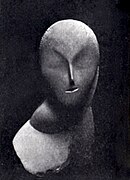

Andrew Dasburg, c. 1912, Lucifer, plaster of Paris, no. 647 of the catalogue. Dasburg extensively reworked by carving directly into a sculpture of a life-size plaster head by Arthur Lee.[32]

-

Abastenia St. Leger Eberle, 1912–13, The White Slave. Photograph from The Survey, Journal Publication, Ohio, May 3, 1913

-

John Frederick Mowbray-Clarke, c. 1912, Group, sculpture, Armory show postcard

-

Wilhelm Lehmbruck, 1911, Femme á genoux (The Kneeling One), cast stone, 176 × 138 × 70 cm, Armory Show postcard

-

Raymond Duchamp-Villon, 1910–11, Torse de jeune homme (Torso of a young man), terracotta, 60.4 cm (23+3⁄4 in), Armory Show postcard, published 1913. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

-

Jacob Epstein, The Rock Drill, 1913, in its original form, it is now lost.

-

Antoine Bourdelle, Herakles the Archer, 1909

-

George Grey Barnard, The Birth, c. 1913, marble

Special installation

[edit]La Maison Cubiste (Cubist House)

[edit]

At the 1912 Salon d'Automne an architectural installation was exhibited that quickly became known as Maison Cubiste (Cubist House), signed Raymond Duchamp-Villon and André Mare along with a group of collaborators. Metzinger and Gleizes in Du "Cubisme", written during the assemblage of the "Maison Cubiste", wrote about the autonomous nature of art, stressing the point that decorative considerations should not govern the spirit of art. Decorative work, to them, was the "antithesis of the picture". "The true picture" wrote Metzinger and Gleizes, "bears its raison d'être within itself. It can be moved from a church to a drawing-room, from a museum to a study. Essentially independent, necessarily complete, it need not immediately satisfy the mind: on the contrary, it should lead it, little by little, towards the fictitious depths in which the coordinative light resides. It does not harmonize with this or that ensemble; it harmonizes with things in general, with the universe: it is an organism ...".[33] "Mare's ensembles were accepted as frames for Cubist works because they allowed paintings and sculptures their independence", writes Christopher Green, "creating a play of contrasts, hence the involvement not only of Gleizes and Metzinger themselves, but of Marie Laurencin, the Duchamp brothers (Raymond Duchamp-Villon designed the facade) and Mare's old friends Léger and Roger La Fresnaye".[34] La Maison Cubiste was a fully furnished house, with a staircase, wrought iron banisters, a living room—the Salon Bourgeois, where paintings by Marcel Duchamp, Metzinger (Woman with a Fan), Gleizes, Laurencin and Léger were hung—and a bedroom. It was an example of L'art décoratif, a home within which Cubist art could be displayed in the comfort and style of modern, bourgeois life. Spectators at the Salon d'Automne passed through the full-scale 10-by-3-meter plaster model of the ground floor of the facade, designed by Duchamp-Villon.[35] This architectural installation was subsequently exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show, New York, Chicago and Boston,[36] listed in the catalogue of the New York exhibit as Raymond Duchamp-Villon, number 609, and entitled "Facade architectural, plaster" (Façade architecturale).[37][38]

Sources

[edit]- Sarah Douglas. "Pier Pressure." March 26, 2008. Archived on April 11, 2008.

- Catalogue of International Exhibition of Modern Art, at the Armory of the Sixty-Ninth Infantry, Feb 15 to March 15, 1913. Association of American Painters and Sculptors, 1913.

- Walt Kuhn. The Story of the Armory Show. New York, 1938.

- Milton W. Brown. The Story of the Armory Show. Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, distributed by New York Graphic Society, 1963. [republished by Abbeville Press, 1988.]

- 1913 Armory Show 50th Anniversary Exhibition. Text by Milton W. Brown. Utica: Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute, 1963.

- Walter Pach Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Walt Kuhn, Kuhn Family Papers, and Armory Show Records, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

See also

[edit]- List of artists in the Armory Show

- List of women artists in the Armory Show

- Experiments in Art and Technology

- American modernism

- American realism

- Ashcan school

- Culture of New York City

- The Armory Show (art fair)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Cotter, Holland (October 28, 2012). "Rethinking the Armory Show". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b International Exhibition of Modern Art, catalogue cover, Copley Society of Boston, Copley Hall, Boston, Mass., 1913

- ^ a b Brown, Milton W. The Story of the Armory Show, Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, New York, 1963, pp. 185–186

- ^ Berman, Avis (2000). As National as the National Biscuit Company; The Academy, the Critics, and the Armory Show, Rave Reviews American Art and Its Critics, 1826–1925. New York: National Academy of Design. p. 131.

- ^ 1913 Armory Show, The Story in Primary Sources (Timeline)

- ^ a b "New York Armory Show of 1913". AskArt.com. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "Securing a Space: The 69th Regiment Armory". 1913 Armory Show: the Story in Primary Sources. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "Walt Kuhn's Itinerary through Europe, 1912". 1913 Armory Show: the Story in Primary Sources. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ Laurette E. McCarthy, Walter Pach, Walter Pach (1883–1958), The Armory Show and the Untold Story of Modern Art in America, Penn State Press, 2011

- ^ "Bloomsday: Court finds Ulysses obscene", New York Irish Arts, June 23, 2012.

- ^ McShea, Megan, A Finding Aid to the Walt Kuhn Family Papers and Armory Show Records, 1859–1978 (bulk 1900–1949), Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ a b Andress, Sarah. "1913 Armory Show Revisited: The Artists and their Prints," Art in Print Vol. 3 No. 2 (July–August 2013).

- ^ Blanke, David. The 1910s. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002. p. 275. ISBN 9780313312519

- ^ Theodore Roosevelt's review of the Armory Show for The Outlook, published on March 29, 1913, was entitled "A Layman's View of an Art Exhibition". See Edmund Morris, Colonel Roosevelt (Random House, New York, 2010; ISBN 978-0-375-50487-7), pages 267–272 and 660–663. According to Morris, Roosevelt's review looked with some favor upon the new American artists.

- ^ Joel Spingarn, p. 110

- ^ Brown, Milton W., The Story of the Armory Show, Joseph H Hirshhorn Foundation, New York, 1963, p. 110

- ^ xroads. Univ. of Virginia

- ^ Cubist Art Will be Investigated; Illinois legislative Investigators to Probe the Moral Tone of the Much Touted Art, Ottumwa Tri-Weekly Courier (Ottumwa, Iowa), 3 April 1913. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress

- ^ "Gallery Map". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on October 7, 2001. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ a b c 1913 Armory Show 50th Anniversary Exhibition 1963 copyright and organized by Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, copyright and sponsored by the Henry Street Settlement, New York City, Library of Congress card number 63-13993

- ^ Vehicle, online. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ documents, history online. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Roberta (February 19, 2009). "Rewards and Clarity in a Show of Restraint". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "The Armory Show at 100". New-York Historical Society. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "1913 Armory Show: The Story in Primary Sources". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 1, 2013.

- ^ "Fountain Art Fair". Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "Celebrating the Armory Show". Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Armory Show". Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Greenwich Historical Society

- ^ "World Premier Film Event: The Great Confusion: The 1913 Armory Show". Connecticut Magazine. Connecticutmag.com. 2013.

- ^ Shircliff, Jennifer Pfeifer (May 2014). Women of the 1913 Armory Show: Their Contributions to the Development of American Modern Art. Louisville, Kentucky: University of Louisville. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Staples, Shelley. "1913 Armory Show: Gallery A Tour". Archived from the original on September 26, 2001.

- ^ "Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinge, except from Du Cubisme, 1912" (PDF). Media Center for Art History - Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 15, 2013.

- ^ Christopher Green, Art in France: 1900–1940, Chapter 8, Modern Spaces; Modern Objects; Modern People, 2000

- ^ La Maison Cubiste, 1912 Archived March 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kubistische werken op de Armory Show

- ^ Duchamp-Villon's Façade architecturale, 1913

- ^ "Catalogue of international exhibition of modern art: at the Armory of the Sixty-ninth Infantry, 1913, Duchamp-Villon, Raymond, Facade Architectural

External links

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

@ The Museum of Modern Art, New York City | |

1913 Armory Show

[edit]- The Armory Show at 100: Modern Art and Revolution, The New-York Historical Society

- Smithsonian, Archives of American Art, Walt Kuhn scrapbook of press clippings documenting the Armory Show, vol. 2, 1913. Armory Show catalogue (illustrated) from pages 159 through 236

- Catalogue of international exhibition of modern art Association of American Painters and Sculptors. Published 1913 by the Association in New York

- 1913 Armory Show: the Story in Primary Sources, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- Virtual re-creation of the Armory Show from the American Studies Programs at the University of Virginia

- Works of art exhibited at the Armory Show of the association of American Painters and Sculptors, New York, Library of Congress

- The Armory Show at 100: Armory Show 1913 Complete List, The New-York Historical Society

Armory shows after 1913

[edit]- The "New" Armory Show

- Artkrush.com feature on the 2006 Armory Show (March, 2006)

- 2010 Armory Show

- Swann Galleries – The Armory Show at 100 – Exhibition through November 5, 2013

- Armory Show 2014: List of exhibiting galleries

40°44′29″N 73°59′03″W / 40.74139°N 73.98417°W

![Andrew Dasburg, c. 1912, Lucifer, plaster of Paris, no. 647 of the catalogue. Dasburg extensively reworked by carving directly into a sculpture of a life-size plaster head by Arthur Lee.[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b4/Andrew_Dasburg%2C_Lucifer%2C_1913%2C_plaster_of_Paris%2C_exhibited_at_the_1913_Armory_show%2C_no._647.jpg/129px-Andrew_Dasburg%2C_Lucifer%2C_1913%2C_plaster_of_Paris%2C_exhibited_at_the_1913_Armory_show%2C_no._647.jpg)